|

|

Previous "Growing Up" articles:

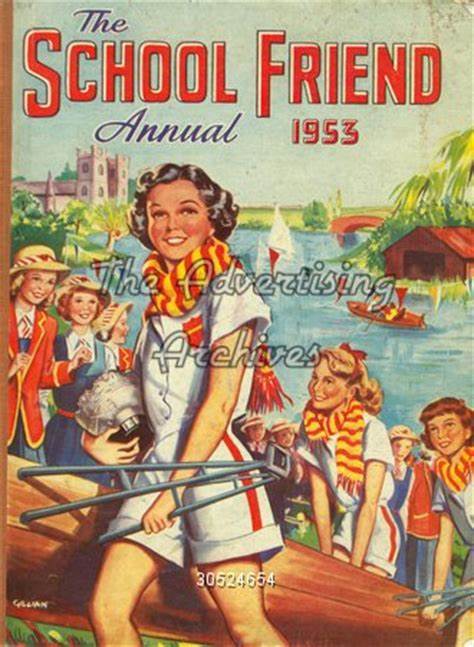

Episode 1 Time to start talking about music and me, I think. I was born into a musical family - that is to say, my Mum played the piano, my Dad played a variety of stringed instruments - we have a photograph of him in fancy dress as a gypsy, playing a violin, but from memory he was never that good on the violin, although he excelled on the mandolin-banjo; my sister Jean, who passed away last month, played the piano, and I played, firstly the recorder (of which more in a moment), then the violin (until the incident with the violin teacher), and finally the guitar, my basic prowess at which I managed to pass on to my two boys, who are both far superior to me; and finally, my violin playing rubbed off on daughter Samantha who went the whole hog and is a Master of Music. So, when I say that I come from a musical family, I'm not talking about more than two generations, I'm talking about my immediate family. My uncles sometimes joined in with stringed instruments such as mandolins, but more often than not they were content to sit and listen as we murdered such classics as Suppé's Poet and Peasant, and tunes from motion pictures such as The Wedding of the Painted Doll. If you were to raise the lid of the piano stool, you would find a massive pile of sheet music, all for the pianoforte. We had one in the house, and my Dad occasionally attempted to tune it, often well enough for Jean to practice her Schubert and her Chopin. There was a time when she was the most gifted musician in the house, but I like to think that when I passed grade three Violin I was starting to overtake her, and by the time I had mastered the basics of guitar playing (jazz and skiffle), she was married and living in a caravan in Charlton Kings, near Cheltenham. Of course, playing an instrument doesn't make you an expert in music. For that, you need to listen. My first instrument, the recorder, was something I was very good at, but it required me to produce a lot of spittle. So much that, my Mum and Dad, being very good with practical jokes of the variety that didn't hurt you mentally, made a cardboard box from a cereal packet (easy, really, just cut the top off) and tied it with string to my recorder. I was so good at the recorder (performing regularly in ensemble at my Primary School), that I was sent down the road a few doors to where Mrs Livesey lived, the piano teacher who had made such a brilliant job of teaching Jean. But, to my dismay, I was no good at piano. My left hand wanted to play the same notes, an octave lower, than my right hand, and vice versa. Later, much later, after many years of playing violin and then guitar, I taught myself to play The Old Rugged Cross on our old piano, achieving a very commendable left hand accompaniment. But my greatest love was the guitar. My earliest memories of listening to music are of Listen With Mother. This would have been from 1950 onwards, when I was walking, and looking at picture books by Mabel Lucy Attwell, and learning to read, and when my ears started to tune themselves to the rather pleasant sounds that came out of the box on the small table in the alcove in the front room next to the bay window. The time was 1:45pm, the introductory music was a few notes on the piano, and then Daphne Oxenford or Julia Lang, who both had the sweetest voices on the radio, asked "Are you sitting comfortably?..... Then I'll begin." And they would start to read to me, stories that featured characters such as Larry the Lamb and Dennis the Dachsund and their adventures in Toytown. The programme finished a quarter of an hour later, with Gabriel Fauré's Dolly Suite. The music is beautiful, the stories were especially tailored for us "baby boomers", children born after 1945 celebrations. I was a baby boomer, sister Jean was a war baby, born in 1941. I miss Jean terribly - we spoke often on the phone; she always looked after me in the early days, and we always got on famously, except for that time when I bought the Beatles' first LP, and played it over and over again downstairs on the radiogram, causing her to make her one and only ccomplaint (that I remember) to my Mum, about playing my music too loud. It was different when she wanted to play her Frank SInatra LPs, of course. But I'm getting ahead of myself. Radio was everything in the 1950s. few people had televisions, at least in our street. Our new next door neighbours, the Hughes family, comprising Ida (mother), father (forget his name), Adrian, Norman and Nigel (the ginger-haired twins) and their sister (forget her name too!), had a television, a nine inch screen which was positioned in the hall, into which we were invited to stand and watch the Coronation in 1953. I imagine they moved the TV into the hall from the lounge, which was always kept shut, except on special occasions (to which we were not privy). The parents were Methodists, very strict, and kept themselves and their home private. They kept up with the Gardners, who lived on the opposite corner, because in their opinion, we were lower in class, probably because we could not afford a television and neither could we afford a car. Both the Hughes family and the Gardner family bought brand new Ford Anglias on the same day... Norman and Nigel, who were rebellious, weren't Methodists, if anything they were unbelievers, never once went in their father's car. At least, that's how it seemed to me. Back to Radio. In those days, there was The Light Programme, The Home Programme, and The Third Programme. With the relaunch of BBC Radio in the 1960s, these became, respectively, Radio 2, Radio 4, and Radio 3. The bulk of the music was to be found on The Light Programme and the Home Programme, unless you had a love of classical music, in which case you tuned to The Third Programme. I had no knowledge or even a liking for classical music in my formative years - that came much later. As a toddler, I listened to every music programme on the radio: Workers' Playtime, Parade of the Pops, Housewives' Choice, Music While You Work, Henry Hall's Music Night, Friday Night is Music Night, Children's Favourites, Two-Way Family Favourites (which often became Three-Way and even, on occasion, Four-Way Family Favourites). Every programme on the BBC had its own theme tune, of course, and on Children's Favourites I would be regaled with all manner of musical treats, like 'Peter and the Wolf', 'The Ugly Duckling', Gilly Gilly Ossenfeffer, Katzenellen Bogen By the Sea', ''The Runaway Train', 'Teddy Bears' Picnic' 'Nellie the Elephant', 'A windmill in Old Amsterdam', 'Sparky's Magic Piano' and my of course, the Oberkirchen Children's Choir singing 'The Happy Wanderer'. As the years progressed and my musical tastes blossomed, I was exposed to simple folk tunes such as Barbara Ellen, and Bobby Shaftoe at school, and various others to which we did country dancing (one of my favourite lessons at school!). I remember one occasion when the Headmaster, a terrifying tyrant called Mr Gillow (whom I didn't like and with whose bullying son I had a run-in in about 1955) brought a gramophone into our lesson and played Smetana's The Bartered Bride Overture. I don't know why, but it made me think about listening to other music - it was exciting, electrifying, hugely enjoyable, and I knew that other music existed because, as I said earlier, we listened to every music programme going, including Mantovani, who murdered various light classical pieces. By this time, I had discovered our own wind-up gramophone, which I believe had a built-in speaker, not one of those giant horns you see in the illustrations of the period, and a stack of 78rpm shellac records of performers like Al Bowlly, Harry Roy and his Band, Jack Hylton and his Orchestra, etc., etc. There was a built-in tray holding the needles you needed to replace on a regular basis. In the next road, my Great Uncle Ernie and Aunt Grace lived. He was OK, she was horrible. But he gave me a pile of 78s to play on my newly discovered toy, for which I was very grateful, finding amongst them,, for example, a performance by Django Reinhardt and the Quintette du Hot Club de France. I was delighted to discover later that day that my Dad also had some Django 78s, and these became the flavour of the month for me, so much so that when my French teacher said we all had to give a five minute presentation (in French) to the rest of the class, I chose to speak about the amazing Django Reinhardt. He was Belgian, not French, but the language was the same, wasn't it? By this time, the world had moved on. To 45rpm single records, and 33-and-a-third rpm albums. On the way home from school in 1958, I went past Currys in the Oxbode in Gloucester. On the opposite side of the road was the massive side profile of the five-storey Bon Marché Department store. But Curry's had what I wanted - a radiogram that not only played all three speeds of record, it also had a radio built in. Our radio, the one that I used to listen to Listen With Mother on, was very old, and past its best. At least as far as I was concerned. Mum, Dad and Jean were happy with it. I was not. I was excited by the prospect of being able to put on an album and not have to get up to change the record, but to sit and listen for anything up to a half hour. In those days I could nag for England, and I nagged and nagged and nagged until Mum caved in and went to Currys and signed a hire purchase agreement for the radiogram. Once it was installed, I had other things on which to spend my pocket money and the money from my paper round besides books and comics. And music was starting to become much more important to teenagers like me. Up till now, we had to get our popular music fixes from Radio Luxembourg on frequency 208. I remember the first LP record I bought - it was a truncated performance of Beethoven's 5th Symphony on the Embassy Record Label, which was exclusive to Woolworths. I'd been with my Dad to a working men's club, which was a smoke-filled room in the middle of Gloucester, where a couple of hundred men stood and listened to a gramophone record recital of the symphony. It blew my mind! And once we had the radiograme, I simply had to have it. Years later I started to buy Classics for Pleasure LPs and discovered that the Embassy 10-inch record missed all of the repeats, and was actually very poor value for money. But at least my record collection was up and running. Some record purchases were hit and miss in those days. Everyone in the family loved traditional jazz, and in the very late 1950s, we heard a performance of Blaze Away, a John Philip Sousa march, by a new band called "Mr Acker Bilk and his Paramount Jazz Band". There was, in those days, I think, a radio programme devoted to jazz. I was duly sent out on Saturday morning to hunt down a copy. In Gloucester, there was Hickey's Music Shop, of which more later, and the Bon Marché department store. Hickeys didn't have the record, and neither did Bon Marché. What the latter did have was a performance of "Whistling Rufus" by Chris Barber's Jazz Band, and with the money Mum, Dad and Jean had given me to buy Blaze Away, I bought Whistling Rufus. There was much disappointment. But in the end I was forgiven, because my Melody Maker newspaper revealed that Blaze Away was on an album and had not been released as a single. By this time, I was hooked on Acker Bilk, and it coincided with "trad jazz" becoming the hottest thing in British music making. Dozens of new bands surged onto the market, with Dick Charlesworth's City Gents, Terry Lightfoot's Band, The Dutch Swing College Band, Chris Barber's Jazz Band, Kenny Ball's Jazz Men, and Mr Acker Bilk and his Paramount Jazz Band, to name just a few. I don't know if it was the name of the band, or the amazingly different and beautiful clarinet of Acker's that hooked me, but for me his was absolutely the best trad jazz band ever, and I set out to follow him and to collect his records. It was about 1961, when Acker changed record labels from the Pye Blue Jazz label to EMI, and at that point, he appointed publicist Peter Leslie, a literary genius, to handle his promotion and to write his record sleeve notes. There is nothing quite like an Accker Bilk sleeve note, which I am in the process of preserving on a special page in Books Monthly. The trad jazz phenomenon was comparatively short-lived, although Acker did shoot to international fame and acclaim with the gorgeous and very memorable Stranger on the Shore, which ensured he was never forgotten, and must have provided him with adequate funds to keep him in comparative luxury until he passed away in 2014. What followed trad jazz in Britain was quite extraordinary, and changed music forever... The thrill of finding out about new albums (and even the occasional single record or EP) by Mr Acker Bilk and His Paramount Jazz Band came about by me buying, every week, the Melody Maker and the New Musical Express. As I recall, there were sections on traditional jazz - and modern jazz, which I abhorred, always have, and always will - in both papers, which regularly listed the top bands, as voted for by the readers, and even twenty or so years after Django Reinhardt and the Quintette disbanded, they still figured in the top tens, because people with longer memories still voted for them. In 1958 or so, Ken Colyer's Jazz Men were still dominating the traditional jazz scene; Acker Bilk had played with them for a few months in the early 1950s before forming his own ensemble, and in their early days, they specialised in "jazzed-up" versions of Sousa marches, such as Blaze Away, Under the Double Eagle, etc., etc., which were released as 78rpm shellac records on the blue Pye Jazz label. Then in 1960, Bilk employed Peter Leslie, an up and coming pulp fiction writer, to be in charge of his publicity. He changed labels, to EMI; Leslie had the idea of dressing the band members in fancy waistcoats and bowler hats, about which I have written extensively on the Acker Bilk Sleeve Notes Page of this magazine, and which has been updated this month with a further selection of Acker's album notes written by Peter Leslie. That same year Acker's single SUMMER SET reached number five in the UK charts, and the floodgates of traditional jazz in Britain were opened. The Wikipedia page says that bands such as Acker Bilk's, Kenny Ball's and Chris Barber's tried to revive traditional jazz in Britain. I know enough about traditional jazz to know that this wasn't a revival - traditional jazz had always been popular with purists, but there was only one Golden Age of traditional jazz in Britain, and that was in the early 1960s. Those bands weren't "reviving" anything, they were playing the music that they had always loved, emulating their 1920s heroes (Jelly Roll Morton, King Oliver, Louis Armstrong's Hot Five etc.), and the British public liked what they heard and trad jazz became the dominant music genre for at least a couple of years, fading away in 1962 as the Beatles wrought the biggest revolution in popular music not just in Britain but all over the world. The 1920s in Britain had seen the boom in "swing" orchestras, like Harry Roy, Jack Hylton etc., and this genre also boomed in Britain in the early 1960s with The Temperance Seven. But the dominant two bands were Acker Bilk's and Kenny Ball's, who had a string of top 40 hits. For me, there was only ever Acker Bilk - or Mr Acker Bilk, as Peter Leslile defined him - and his Paramount Jazz Band. They were far and away the very finest musicians on the trad jazz circuit, and if you listen to Jelly Roll Morton's classic single "Doctor Jazz" and compare it with Acker's "Stomp Off, Let's Go", you can hear what Acker was trying to achieve, and how brilliantly he succeeded. There is footage on YouTube of Acker and his band playing "In a Persian Market Place", a light classical "bonbon" by Ketelbey, arranged by Acker, showcasing the brilliance of the Paramount Jazz Band in all its glory. I urge you to watch it, it is terrific, and shows an ensemble at the top of its game. The other reason for my choosing Acker above all others in the trad jazz field is the plethora of literature produced by Peter Leslie's BILK MARKETING BOARD, which was the name of the publicity machine that ensured that Acker dominated the trad jazz phenomenon that swept Britain from 1960-1962. When Acker wrote a tune which he called "Jenny" after his daughter, (subsequently renamed Stranger on the Shore to accompany a hugely successful children's TV serial) I was delighted, because it meant that my hero (who hailed from the West Country, just as I did) would still be dominating the charts even though music was changing in Britain. The announcement of the album, with Acker backed by the Leon Young String Chorale, was made in the NME and Melody Maker, with the caveat that it would be issued in the United States about five months before it would be released in Britain. I was by that time a subscriber to a record company - like the Companion Book Club, which sent you a monthly selection which you could keep or return - and they also announced the US release of the Stranger On the Shore Album. I ordered it through them, which meant that I had the precious LP in my hands five months before it was released over here; and I treasured it just like all of the other Acker Bilk albums. The sleeve notes were again written by the marketing and literary genius, Peter Leslie, and you'll find this on the Acker Bilk page in Books Monthly, too. Trad Jazz, and particularly Acker Bilk's renderings of it, have remained favourites of mine right up to the present day. Most of those brilliant Acker Bilk albums have been released as CDs, but the CD producers have not recognised how important the sleeve notes were and are, which is why I have taken it upon myself to reproduce them in Books Monthly. It is literature, after all. The late 1950s and early 1960s are imprinted on my memory as my Golden Age of music - or discoveries, of passions, of formative years. In 1958 my dear Gran died. I only ever had one grandparent, the other three all died before I was born. She was precious to me - I have only the fondest memories of her. In 1958 I was eleven years old (when she died - I reached twelve later in the year). Mum and Dad decided I might be too young to attend her funeral, and so I was packed off to spend the day with sister Jean in her place of work in Cheltenham, in a Grace Bros., style store called Wolfe and Hollander, where she worked as a secretary. I was given a ten shilling note (a fortune in those days) and told to go and spend it, to buy something I really wanted, so that the day would be remembered as a good one, and not as a dark one, the day they buried Gran. I went first into a branch of W H Smith and bought THE ADVENTURES OF SHERLOCK HOLMES, and then into a record shop, where I bought THE BALLAD OF TOM DOOLEY by the KINGSTON TRIO. I was heavily into my music by then, books and music were my principal hobbies. When the weather was too bad for outdoor play, like football, I was happy to sit in the front room playing my records and reading my books.  Like my three children

after me, I

always maintained that I could do my homework with my music playing in

the background. It worked for me, and it worked for them! At school,

the arguments raged about who was best - Elvis Presley or Cliff

Richard. One of my rivals for being best at Spanish, a boy we called

"Pedro" Smith (Smith was his real name, Pedro was his nickname, first

name was really Peter), insisted on championing Elvis, but for the

purposes of just being different, I championed Cliff Richard - even

though he didn't interest me at all. If anything, he was a bit wet for

me, but I was happy to debate the various records of the two men who

dominated pop music in 1958 and on into the beginning of the 1960s. In

1962, recovering from my abuse at the hands of the peripatetic violin

teacher, with whom I reached and passed Grade 3, I was looking for a

musical challenge, for the violin had lost its appeal. I found an old

guitar in a cupboard upstairs at home, and tuned it so that it played a

chord. I spent hours teaching myself to play, sitting in front of the

big mirror in Mum and Dad's room, and then realised that I should

really be tuning it properly. This I did, and set about teaching myself

all over again, sometimes with the aid of the Bert Weedon book,

sometimes without. This coincided with my discovery of the breathtaking

genius of Django Reinhardt - I even gave a speech in my class about

Django, all in French, it was something we all had to do, and I chose

to talk about a Belgian! But as well as the 78rpm records Dad had dug

out of his collection, there were leaflets, concert programmes, sheet

music, many of which had pictures of Django, some of which showed him

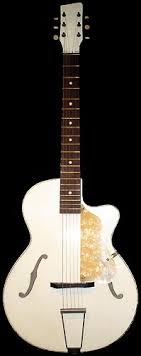

playing that amazing Macaferri guitar. I had to have a guitar of my

own, and it had to look something like Django's. So off I went to

Hickey's the big music shop in Northgate, in Gloucester city centre,

and looked for a guitar with a cutaway, at a price I could afford. I

found one which probably looked more like Roy Rogers's guitar, but

never mind. It was a Rosetti guitar, white with a thin dark line all

the way round the edge. The one pictured doesn't have the edge stripe,

but it's identical in every other respect. My eldest son Martin still

has it. My guitar cost £3, and I paid a deposit of ten shillings, the

remainder to be paid in weekly instalments, which took most of my paper

round money. At last I had a decent guitar of my own, and, what was

more important, I could play it! Like my three children

after me, I

always maintained that I could do my homework with my music playing in

the background. It worked for me, and it worked for them! At school,

the arguments raged about who was best - Elvis Presley or Cliff

Richard. One of my rivals for being best at Spanish, a boy we called

"Pedro" Smith (Smith was his real name, Pedro was his nickname, first

name was really Peter), insisted on championing Elvis, but for the

purposes of just being different, I championed Cliff Richard - even

though he didn't interest me at all. If anything, he was a bit wet for

me, but I was happy to debate the various records of the two men who

dominated pop music in 1958 and on into the beginning of the 1960s. In

1962, recovering from my abuse at the hands of the peripatetic violin

teacher, with whom I reached and passed Grade 3, I was looking for a

musical challenge, for the violin had lost its appeal. I found an old

guitar in a cupboard upstairs at home, and tuned it so that it played a

chord. I spent hours teaching myself to play, sitting in front of the

big mirror in Mum and Dad's room, and then realised that I should

really be tuning it properly. This I did, and set about teaching myself

all over again, sometimes with the aid of the Bert Weedon book,

sometimes without. This coincided with my discovery of the breathtaking

genius of Django Reinhardt - I even gave a speech in my class about

Django, all in French, it was something we all had to do, and I chose

to talk about a Belgian! But as well as the 78rpm records Dad had dug

out of his collection, there were leaflets, concert programmes, sheet

music, many of which had pictures of Django, some of which showed him

playing that amazing Macaferri guitar. I had to have a guitar of my

own, and it had to look something like Django's. So off I went to

Hickey's the big music shop in Northgate, in Gloucester city centre,

and looked for a guitar with a cutaway, at a price I could afford. I

found one which probably looked more like Roy Rogers's guitar, but

never mind. It was a Rosetti guitar, white with a thin dark line all

the way round the edge. The one pictured doesn't have the edge stripe,

but it's identical in every other respect. My eldest son Martin still

has it. My guitar cost £3, and I paid a deposit of ten shillings, the

remainder to be paid in weekly instalments, which took most of my paper

round money. At last I had a decent guitar of my own, and, what was

more important, I could play it! The small print: Books Monthly, now well into its 24th year on the web, is published on or slightly before the first day of each month by Paul Norman. You can contact me here. If you wish to submit something for publication in the magazine, let me remind you there is no payment as I don't make any money from this publication. If you want to send me something to review, contact me via email at paulenorman1@gmail.com and I'll let you know where to send it.

|

|

,

|