|

|

Previous "Growing Up" articles:

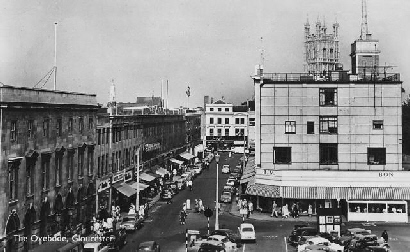

March 2022 - The Oxbode, Gloucester

On this month's Growing Up in the 1950s page I need to start with an apology: in previous "essays" on this page I asserted that I had attended a small school in Shurdington for six months prior to the opening of the brand new Brockworth New County Primary School. I knew for sure that the bus turned right at the crossroads, the only problem with that being that Shurdington was left, on the way to Cheltenham. It turns out I was wrong - I didn't attend the little school at Shurdington, I went to an even smaller school at Cranham, up behind Cheeseroll Hill. Here's an excerpt from the history of Cranham and its school from the Gloucestershire History Archives: "

In

1948 there were 11 children on the roll"...

In 1950, I was one of sixteen. Somewhere in my collection of old photos

there's one of the entire school, all sixteen of us, including me and

my sister Jean. The

reason I made

this discovery was because this month's BBC Music Magazine has an

article on the Gustav Holst Walking Trail, which begins in Cranham,

Holst's birthplace, about two miles away from my own birthplace, in

Brockworth. I'm glad we got that cleared up, because it had been

nagging at me, realising that the bus to Shurdington going left instead

of right was all wrong! This month I want to talk more about

Gloucester, and in particular one very notable street: The Oxbode. The

Oxbode ran along past the gigantic Bon Marché store towards Eastgate,

and I think my family and I, but particularly me, spent more money in

that street than any other street in Gloucester, at least for a while.

In the 1950s, on the left hand side of the Oxbode, coming out of Kings

Square, there was a branch of Currys, and a toy shop. The toy shop

window was filled with the latest Dinky and Corgi toys. If you've

looked at this month's nostalgia page, you will have seen the new book

from Veloce about the Triumph TR2 and TR3 motor cars. One day, whilst

in the Oxbode, I happened to glance in the toyshop window and there was

Dinky Toy Number 111 - the Triumph TR2. This was the most beautiful car

I had ever seen in my life. I would have been six or seven years old,

and well into toy cars, with a growing collection. I had to have the

Triumph TR2 model, and made a promise to myself that when I was old

enough, I would have the real thing. In

1948 there were 11 children on the roll"...

In 1950, I was one of sixteen. Somewhere in my collection of old photos

there's one of the entire school, all sixteen of us, including me and

my sister Jean. The

reason I made

this discovery was because this month's BBC Music Magazine has an

article on the Gustav Holst Walking Trail, which begins in Cranham,

Holst's birthplace, about two miles away from my own birthplace, in

Brockworth. I'm glad we got that cleared up, because it had been

nagging at me, realising that the bus to Shurdington going left instead

of right was all wrong! This month I want to talk more about

Gloucester, and in particular one very notable street: The Oxbode. The

Oxbode ran along past the gigantic Bon Marché store towards Eastgate,

and I think my family and I, but particularly me, spent more money in

that street than any other street in Gloucester, at least for a while.

In the 1950s, on the left hand side of the Oxbode, coming out of Kings

Square, there was a branch of Currys, and a toy shop. The toy shop

window was filled with the latest Dinky and Corgi toys. If you've

looked at this month's nostalgia page, you will have seen the new book

from Veloce about the Triumph TR2 and TR3 motor cars. One day, whilst

in the Oxbode, I happened to glance in the toyshop window and there was

Dinky Toy Number 111 - the Triumph TR2. This was the most beautiful car

I had ever seen in my life. I would have been six or seven years old,

and well into toy cars, with a growing collection. I had to have the

Triumph TR2 model, and made a promise to myself that when I was old

enough, I would have the real thing. That

sadly never happened, but I did get my model, and I played with it all

the time, selecting it from my collection and preferring it to all

others. When friends came to play, I would never let them play with the

TR2, that remained hidden in a drawer until they had gone home to their

own toy car collections. When one of the part-work companies launched

their Dinky Toys collection a few years back, I was pleased to see that

the first issue, which cost £2.99, I think (probably more than ten

times what I paid for me model 111 back in 1953-4) was model number

111, the TR2, and I was one of the first people to buy one in my home

town. I have no way of knowing that, but it felt that way to me. To

have my favourite model car in pride of place in the cabinet meant so

much to me! A few years later, at the age of ten, I was set to become a

paper boy at Mr Lees post office-cum-newsagent-cum-general-store in

Ermine Street. I had to wait until I was eleven, which was in a month's

time, but he had interviewed me (I was accompanied by my Mum) and

agreed that I was ideal for the job.

In

preparation, I started to save my pocket money in readiness to put a

deposit on a bicycle. I didn't have one - all I had was the red Triang

tricycle that saw me through my toddler years, and at the age of

eleven, it would have been far too small, although the boot would have

been very good for putting the newspapers and magazines in! My Mum and

I went one day to the Oxbode, to Currys. Upstairs, there must have been

around fifty or sixty brand new bicycles, hanging from the ceiling, and

hundreds more standing on the upper sales floor. I selected a Raleigh

four-speed with drop handlebars in black and yellow, and paid my

deposit. A few weeks later, having paid in full, a Currys van stopped

outside our house and the driver extracted my gleaming new bike from

the back and handed it to me. It was immediately appropriated by the

ginger-haired twins from next door, both of whom were green with envy.

Their bikes had straight handlesbars and only three gears! Eventually

they let me ride it up and down Boverton Drive, and the next morning,

at 5:30am I set off down the road to do my first newspaper delivery on

my new bike. I went everywhete on that bike, all over Brockworth,

Churchdown, Hucclecote, Cranham Woods, everywhere. I even started

riding the seven miles from home to school, and continued to do so

until I left in July 1963 to start my new life in Stevenage New Town,

whose revolutionary cycle tracks made it a joy to ride a bike.

But

I digress, and it's time for two last incidents of money changing hands

in the Oxbode! Still in my first year at the Crypt Grammar School, I

was used to getting two buses home. The first dropped me in Westgate,

followed by a walk to Kings Square, which involved walking along the

Oxbode, and there, one late afternoon in 1958, outside Currys (of all

places!) stood a handsome new radiogram. At home, we currently had a

radio that sat on the shelf in the front room, and a wind-up gramophone

which sat in a cupboard and only came out when someone in the family

wanted to listen to those old 78rpm shellac records of Al Bowlly, or

Jack Hylton and his orchestra. Also in 1958, I discovered Dad's small

collection of Django Reinhardt 78s and played them to death. There

seemed to be a never-ending supply of needles for the gramophone.

But

things were starting to change in the entertainment industry, and every

single boy in my class except me, had a record player! That was how I

pitched it to my Mum, and after days of nagging, she met me one

afternoon on the way home from school, and bought the radiogram on six

months' credit terms, which meant it could be delivered immediately and

I would help Mum with the repayments from my paper round money. This

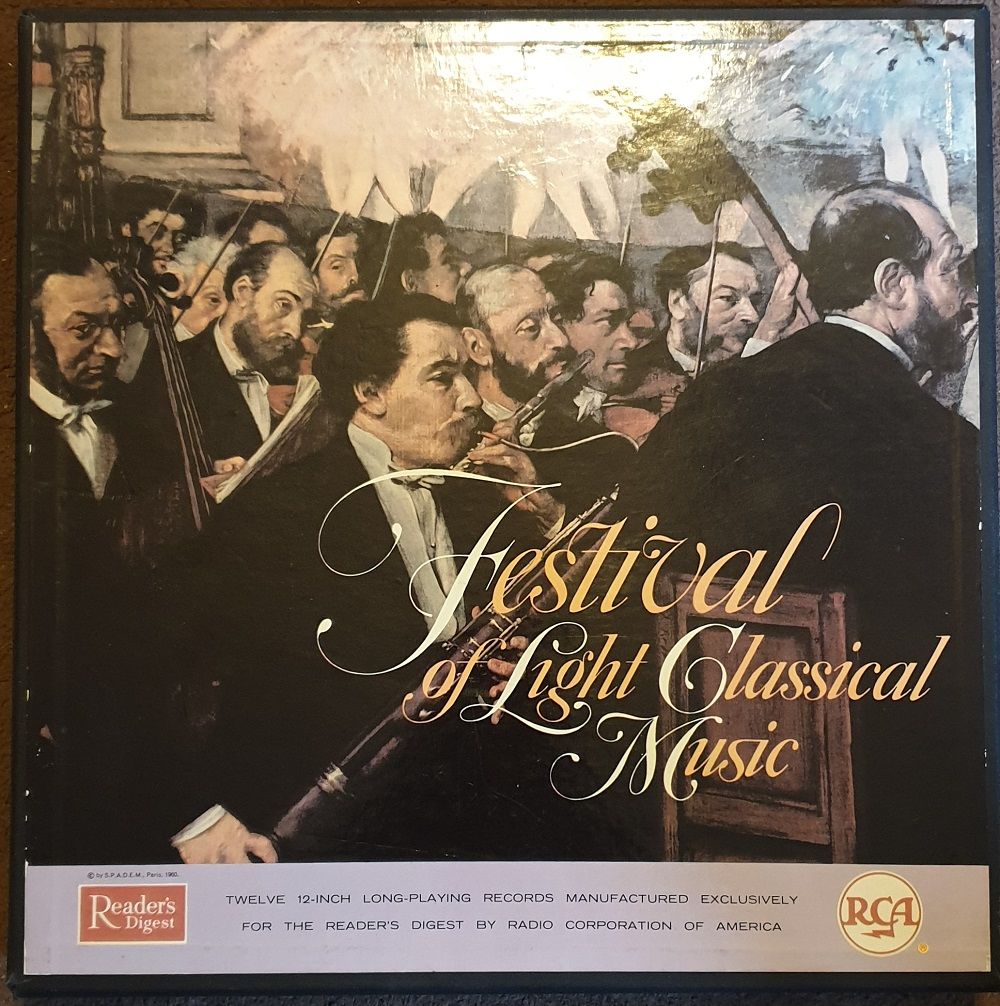

meant that I could buy 45rpm singles, and 33rpm LPs. The first LP I

bought came not from the Oxbode, although they did sell them in Bon

Marché, but from Woolworths, and it was a 10-inch LP Of Beethoven's

Fifth Symphony, a record recital of which I had attended in a working

men's club with my Dad a few weeks previously - standing room only,

amongst a hundred or so working men, all twice my height and all

smoking like chimneys. A very unpleasant experience alleviated only by

the sheer glory of the music, a piece I simply had to have. With the

new radiogram in pride of place in the front room bay window, I started

to accumulate 78rpm records like there was no tomorrow, eventually

discovering Acker Bilk, Lonnie Donegan and others from Brian Matthew's

brilliant Saturday morning record programme on the BBC Light Programme.

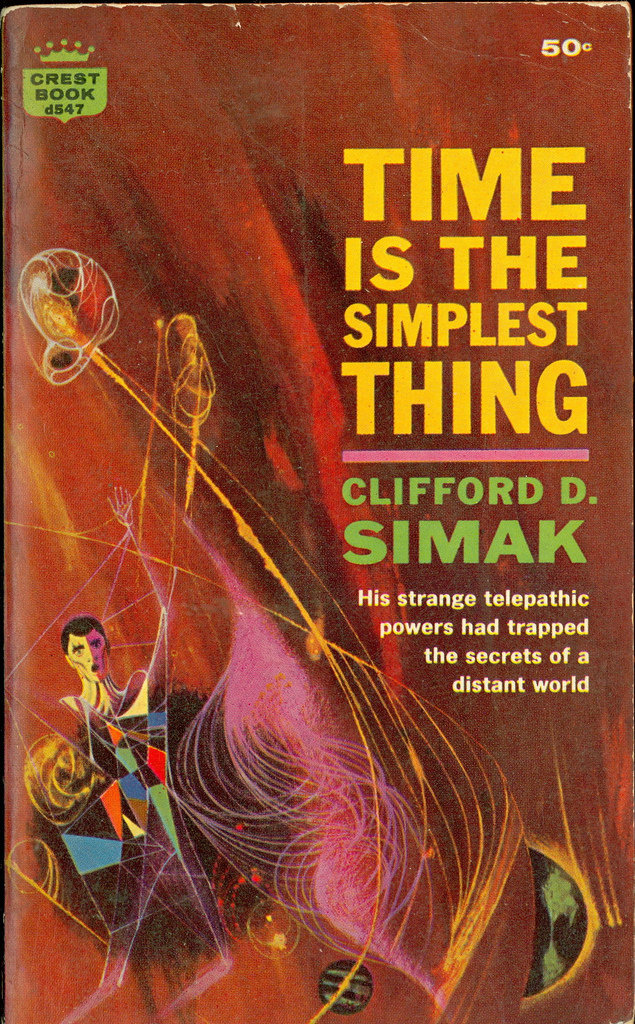

But LPs were the way to go - in 1959 I discovered an LP by Django

Reinhardt and the Quintette du Hot Club de France. That same year I

started to buy Acker Bilk LPs (you'll find them all on the Acker Bilk

page); and in 1961 I discovered Bobby Darin and the Beatles, and the

rest is history. Eventually all of my records came from Bon Marché,

where they had listening booths, and in July 1963, as I said earlier,

we moved from Boverton Drive to Southend-on-Sea where we stayed with

Uncle Stan and Aunt Florrie until November, when it was time to move to

Stevenage, and the second major phase of my life began, where and when

I would meet Wendy, we would fall in love, get married and spend the

next 56 years of our lives together... (to be continued).

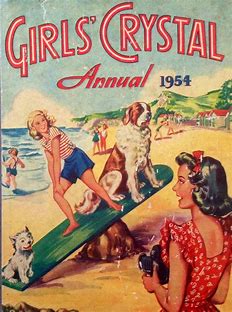

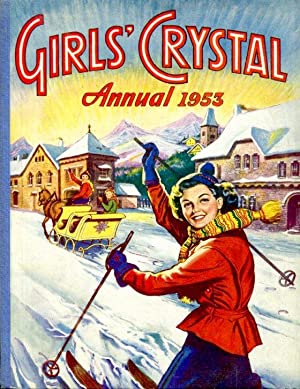

FEBRUARY 2022: This

month I'm running out of time, so I thought I would just share with you

what a typical 1950s/1960s Christmas was like for me and my sister

Jean... Let's take 1956, I was ten years old, Jean would have been

fourteen. I was a third of the way through my last year at Brockworth

New County Primary School, because my birthday was in mid September and

I was deemed ready to take the 11+ exam the following June, which

meant, if I were to pass, that I would move up to senior school in July

of 1957. I wasn't fazed by the thought of this exam, and I wasn't

really conscious of the fact that I would be taking the exam a year

early, because it wasn't really a year early to me, it was just a few

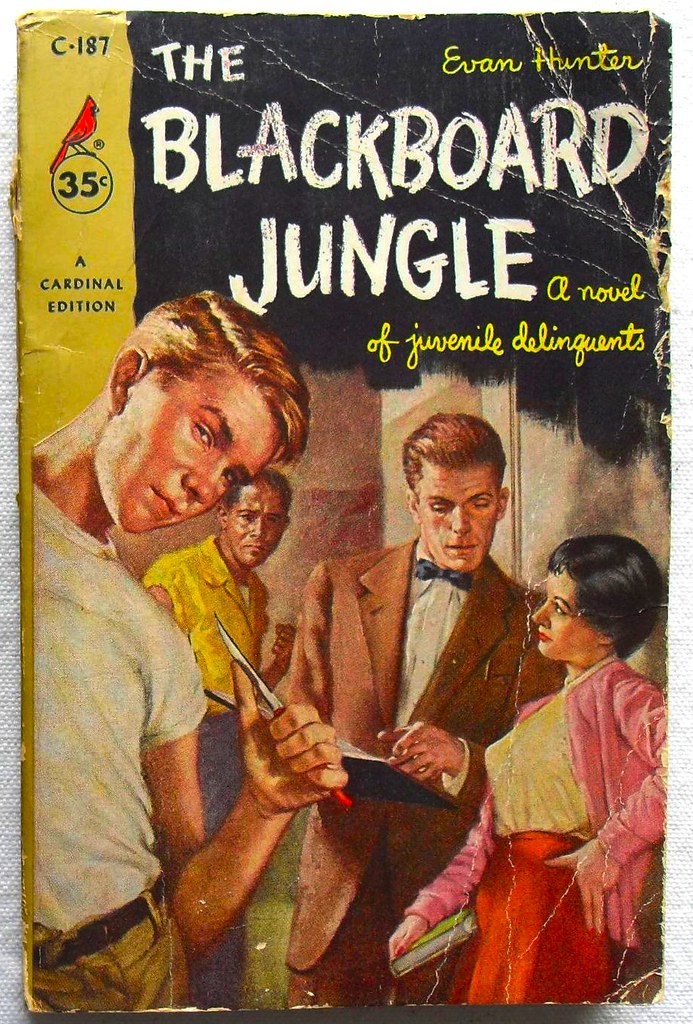

months, three, to be precise. I had the reading age of a sixteen year

old, I had many Charles Dickens titles in my own collection, as well as

R M Ballantyne, Robert Louis Stevenson, Alexander Dumas, etc., etc.,

all normal reading matter, I thought, for a ten year old. I also had

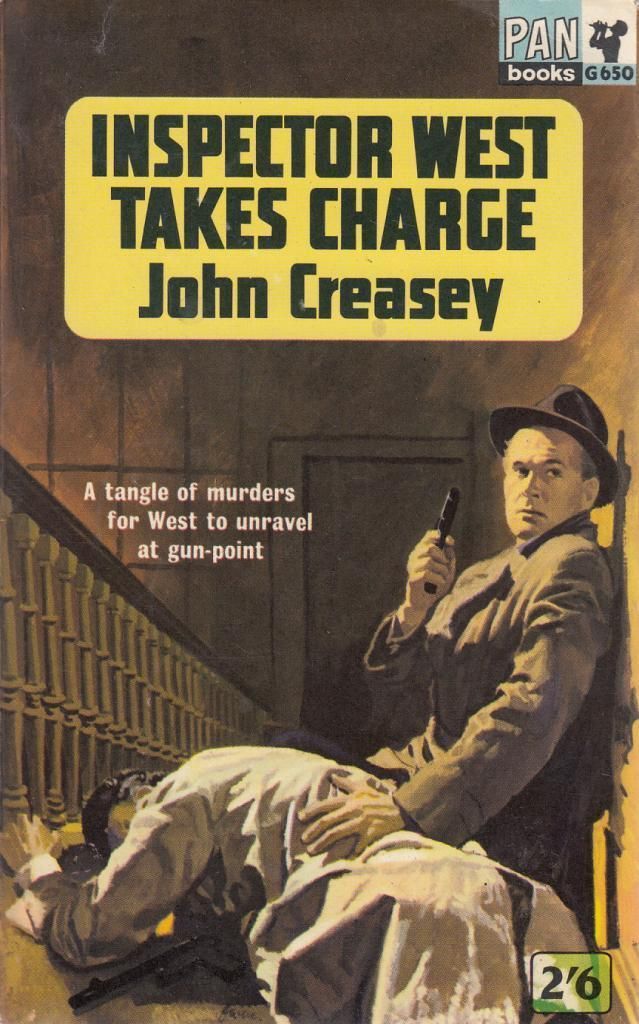

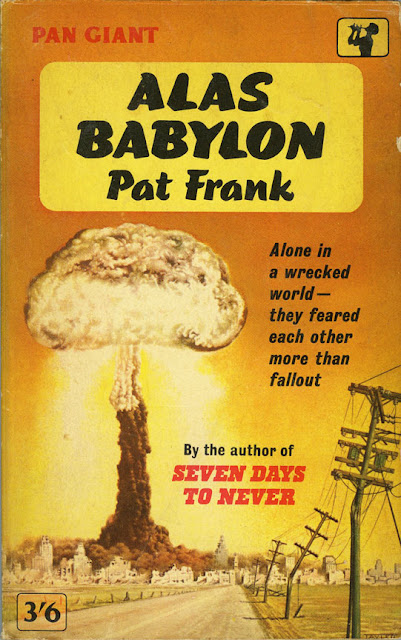

almost a complete set of Leslie Charteris's Saint books, some Inspector

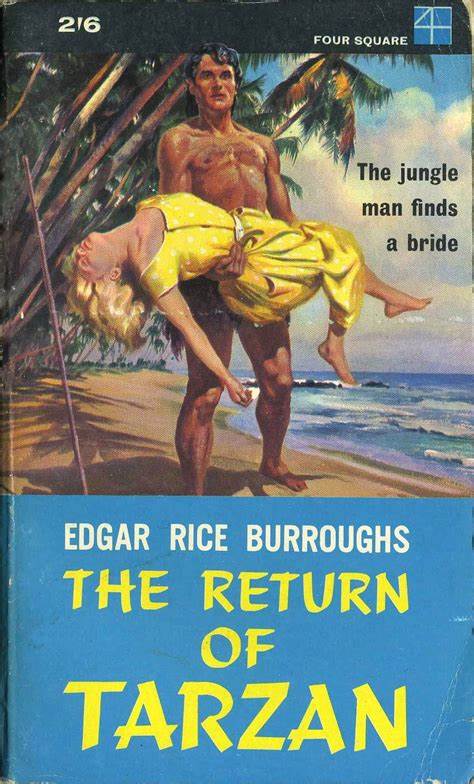

Wests, some Pan Horror Stories anthologies, Lorna Doone, Robin Hood and

King Arthur, the latter two being my absolute favourites... and some

Tarzan books. FEBRUARY 2022: This

month I'm running out of time, so I thought I would just share with you

what a typical 1950s/1960s Christmas was like for me and my sister

Jean... Let's take 1956, I was ten years old, Jean would have been

fourteen. I was a third of the way through my last year at Brockworth

New County Primary School, because my birthday was in mid September and

I was deemed ready to take the 11+ exam the following June, which

meant, if I were to pass, that I would move up to senior school in July

of 1957. I wasn't fazed by the thought of this exam, and I wasn't

really conscious of the fact that I would be taking the exam a year

early, because it wasn't really a year early to me, it was just a few

months, three, to be precise. I had the reading age of a sixteen year

old, I had many Charles Dickens titles in my own collection, as well as

R M Ballantyne, Robert Louis Stevenson, Alexander Dumas, etc., etc.,

all normal reading matter, I thought, for a ten year old. I also had

almost a complete set of Leslie Charteris's Saint books, some Inspector

Wests, some Pan Horror Stories anthologies, Lorna Doone, Robin Hood and

King Arthur, the latter two being my absolute favourites... and some

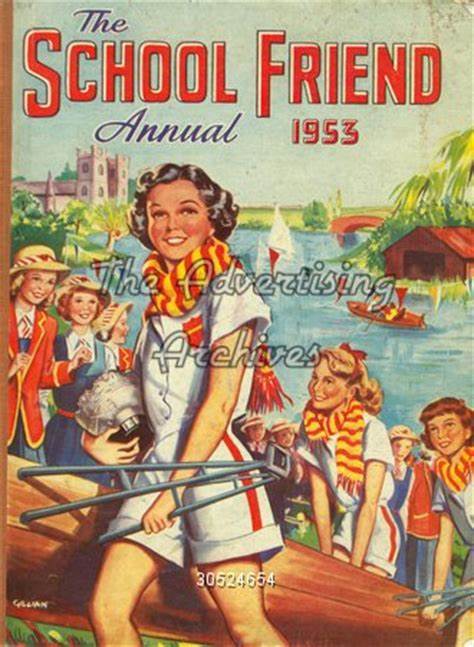

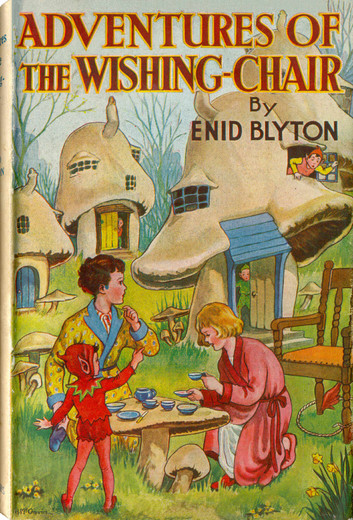

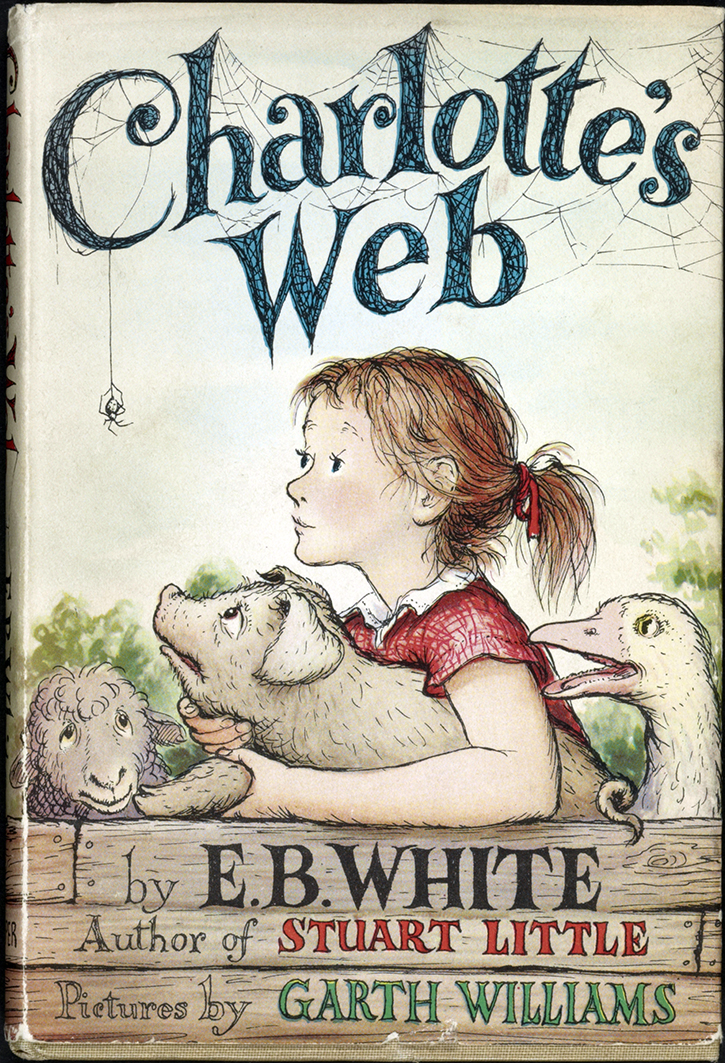

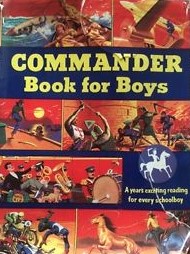

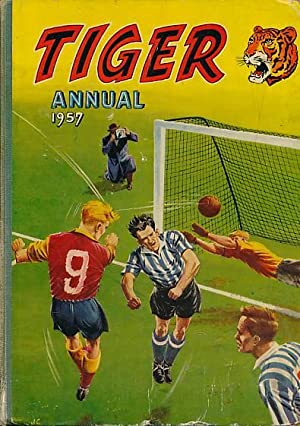

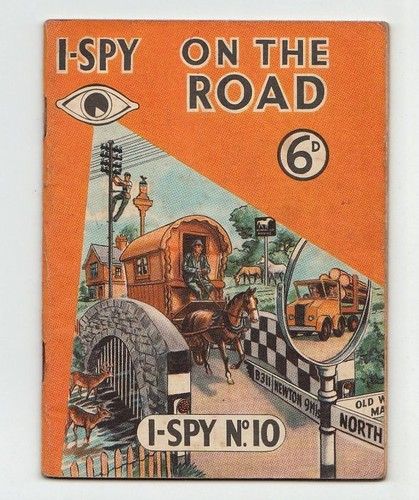

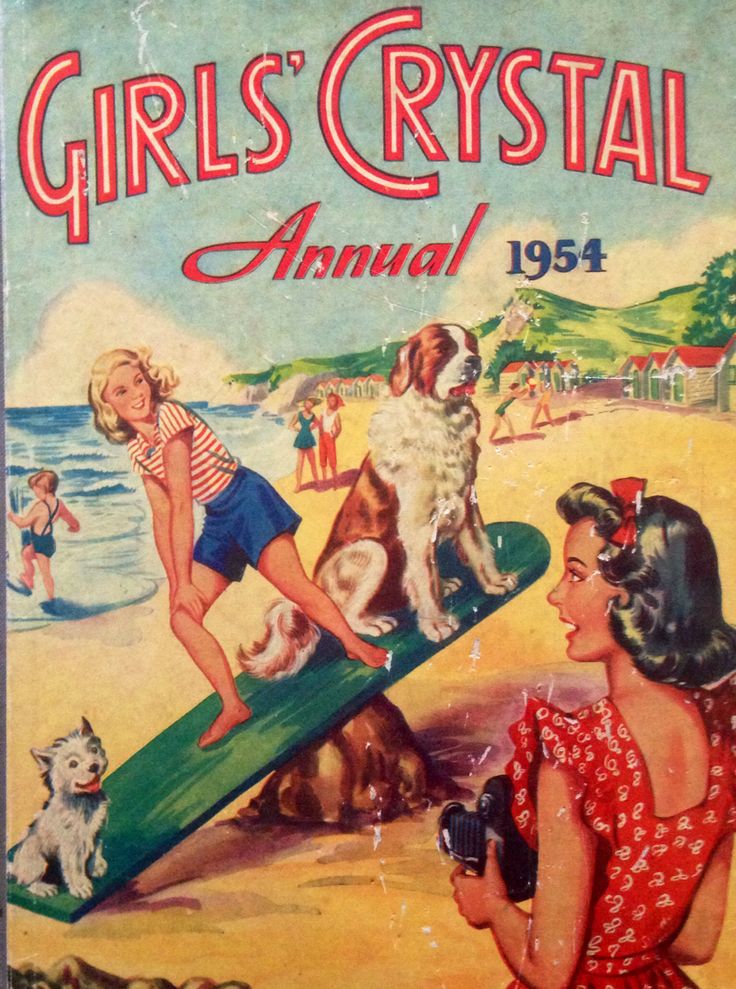

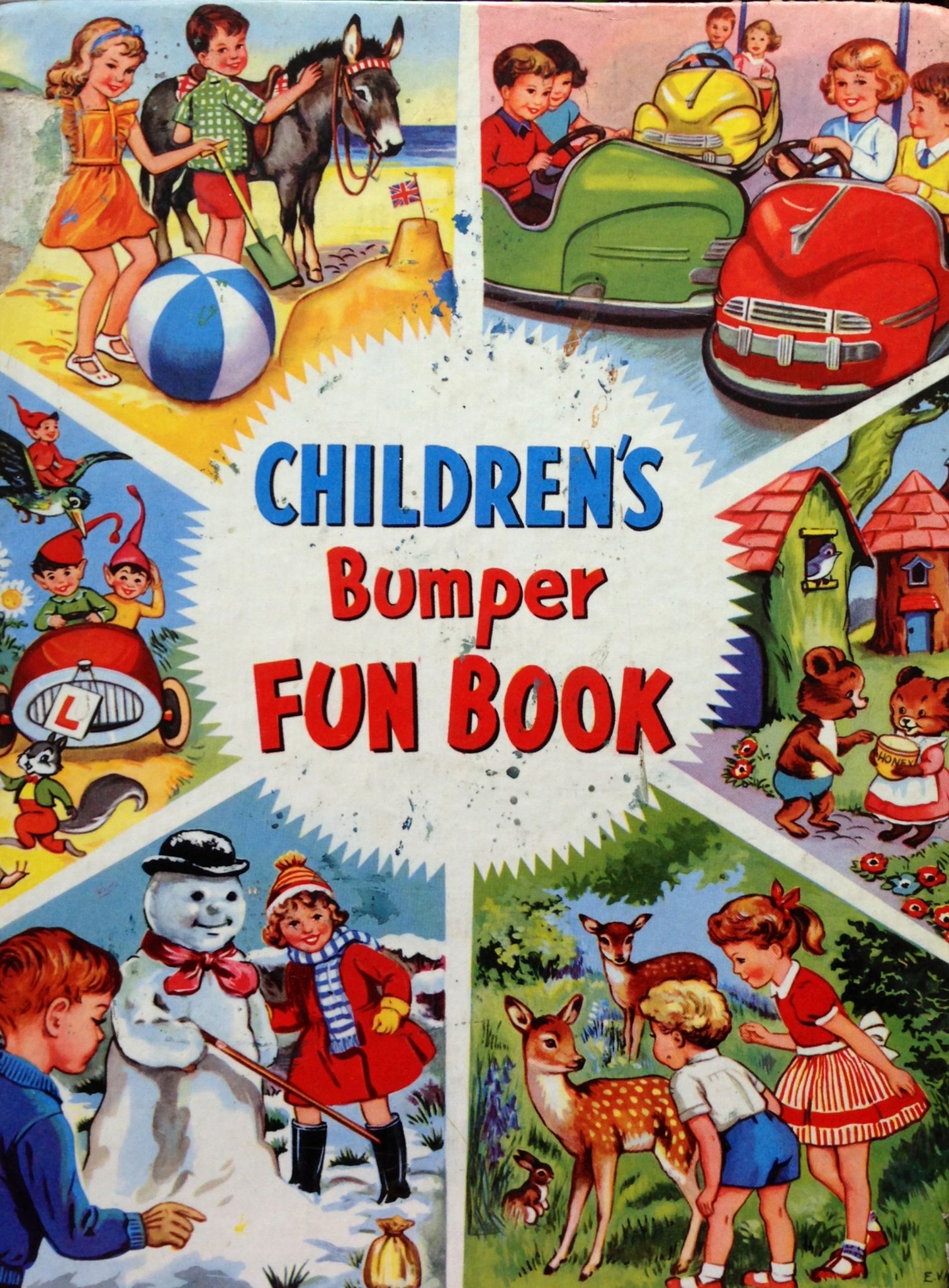

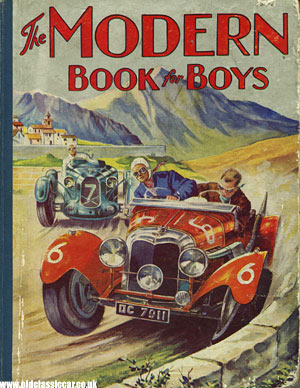

Tarzan books. We were always asked what we would like for Christmas, and, taking the Tiger and Lion comics every week, I was aware of but not particularly interested in football, to the extent that some of my friends were. However, at the beginning of every football season, in September, the Tiger provided a carboard insert that allowed you to move teams up and down as the results came in; I was always a sucker for a free gift in my comics, and as I enjoyed a kickabout with my friends, I decided to ask for a football. In those days, footballs were made of leather and were inflated using an adaptor on a bicycle tire pump. I didn't have a bicycle then, that came a year or so later when I was eleven years old and able to take on a paper round. I bought the bicycle myself, a Raleigh four-speed, which was the envy of all my friends, especially the ginger-haired twins next door, as their bicycles were not equipped with drop handlebars, and had only three gears! Back to Christmas... I desperately wanted a three-colour torch - basically a normal torch with a sliding mechanism that placed a red or a green plastic lens over the bulb; cool! Other than that, I asked for the usual: a tin of toffees, either Sharps toffees or Bluebird toffees, a box of Turkish Delight, and my usual annuals, the Tiger and the Lion. I remember hanging a stocking at the end of my bed, and in the morning it had mysteriously been replaced by a pillow case... and in it was a cubic box containing my leather football; a three-colour torch; an orange and an apple; a tin of Sharps toffees; a wooden box of Turkish Delight; my Lion Annual and my Tiger annual, and another rectangular parcel which felt like another book, only it was three times as thick as my 160-page Tiger and Lion anuals. Because 1956 was the first year in which the Commander Book for Boys was published - a massive book containing over five hundred pages of beautifully illustrated stories (by Robert McGillivray) for boys - school stories, Wild West stories, desert island stories, etc., etc. I was overjoyed. This was a handsome book, some two inches thick, the same size as a TIger annual, and with a dustjacket - a beautifully illustrated brightly coloured dustjacket. The Commander book was published for four years running, and I still have all four of mine, all with their dustjackets. I have two of the companion girls' books, too, the Coronet Book for Girls, which Jean had each year in her pillow case. We scratched around and found a bicycle pump and got the football inflated. Dad and I had a glorious kickabout on the front lawn, then went inside to chill out, me with my three treasured books, and to start eating my toffees while Mum and Jean started preparing the Capon for Christmas dinner, and Dad went to the pub with Mum's brothers, my uncles John and Ernie. Christmas dinner would comprise the four of of us, the two uncles, and my beloved Gran. Later in the day other relatives would join us and we would spend the evening singing songs while Mum played the piano and Dad played the mandolin-banjo. All I could play at that stage of my life was the recorder, and not well enough to join in with the old favourites. There was always a houseful at Christmas - sometimes Dad's sisters, Aunt Ivy and Florrie would come to stay from Hornchurch in Essex, bringing with them their husbands, George and Stan, and Sylvia, Aunt Ivy and Uncle George's daughter, with whom I was madly in love. She was about eighteen months older than me, and I dreamed of growing up and marrying her. It didn't happen, of course, although legally I think it would have been within the law for it to happen. At bedtime, I started to read my Commander Book for Boys, and when it was time for lights out, I used my new torch to carry on reading by torchlight until I was too tired to stay awake. You may be wondering what gifts I bought for my Mum and Dad that year - well, it was the same as every other year, it was California Poppy scent for Mum, and a box of Dairy Milk; and a pair of yellow socks for Dad. I only ever remember buying Dad yellow socks at Christmas... When I think about the kinds of money that gets spent on children nowadays, it makes me think of the simple things I would find in my pillow case, and how I was always so thrilled beyond belief to have my three brilliant books, the two comic annuals, and the brand new Commander Book for Boys. Pocket money books, a pocket money torch, pocket money sweets... and a football, which must have cost a comparatively small fortune to Mum and Dad. They weren't cheap, but they meant a huge amount to me. The perfect Christmas - basically, for me, it was books and sweets... JANUARY 2022: The 1950s was the age of the baby boomers, of an end to rationing; it was the first decade of liberation after almost six years of the terror of war. It was an age of bicycles and tricycles, of home-made bows and arrows, of jam jars with string tied round for carrying our ill-gotten gains of newts and leeches from the stream, of long walks in the countryside, of climbing trees, of reading the huge number of children's comics that were available; of listening to the big radio in the front room, to Little Jimmy Clitheroe, Billy Cotton, Life with the Lyons, Hancock's Half Hour, Much Binding in the Marsh, Children's Favourites with Uncle Mac, Children's Hour after school, Mrs Dales's Diary, Listen With Mother, and Radio Luxembourg on a primitive transistor radio. It was the age of Enid Blyton, and Mabel Lucie Attwell, and Robert Louis Stevenson, of R M Ballantyne, of Robin Hood and King Arthur, of Buffalo Bill, Wild Bill Hickock and General Custer, and of treasure islands. Of homework followed by a family dinner, then a kick-about in the council playing fields with school friends, then home to bed and reading a favourite book until lights out... My earliest memory is of me at around six months old, standing up in my cot and screaming in terror as monkeys swarmed up the rope vines that adorned the bedroom wall. I was reliably informed, by my Mum, before she passed away, that the wallpaper in their bedroom at number 72 Boverton Drive, in Brockworth village, Gloucestershire, included a horizontal frieze depicting zoo animans, some of which were indeed monkeys, and that this screaming fit coincided with me having whooping cough, a serious illness that almost did for me back in 1947. Other than that memory, and one of me sitting in a tin bath on the lawn in the side garden, probably a couple of months further on, I have very little memory of the late 1940s, the decade in which I was born except for being allowed to play with local children a little older than me. Having said that, the 1950s were absolutely identical in almost every way to the 1940s except that midway through the 1950s, rationing finally came to an end, and one could say that the war was finally over. I do remember being taken to the Bear Gardens Clinic in Gloucester, some kind of children's health centre, where I was taught, for some obscure reason, to pick up pencils with my toes. To this day I don't know if I have flat feet, or fallen arches, and wouldn't know what either of these afflictions entailed, I only know I went to have some corrective exercises which, whatever they were for, apparently worked. This would have been when I was around three or four years old. I also remember many times going into the city on the bus with Mum and feeling very, very sick, which meant that we would have to get off the bus in Barnwood, around two miles from the city centre, whilst I calmed down, and then we probably went home. Another bus journey I remember well in 1951, when I was just four and a half years old, was the one to the one-class, one-teacher Shurdington Village School. This was just before the opening of the New County Primary School in Brockworth, which I attended until I passed the 11+ exam at the age of ten and graduated to the Crypt Grammar School in Tuffley, Gloucester.  Brockworth

village grew up on the

back of the Gloucester Aircraft Company, which, although many websites

claim was situated in Hucclecote, the next village along Ermin Street

on the way to Gloucester City, was actually situated in Brockworth. The

main entrance was in Brockworth, and there were a couple of miles of

open fields and houses before you got to Hucclecote, although the

grounds of the Gloucester Aircraft Company ran along the back of these

houses and did indeed join Hucclecote to Brockworth. In 1950, the first

year I really remember anything of any significance, Gloucester

Aircraft Company was making the Gloucester Javelin, and every morning

at around ten o'clock, the air raid siren would sound - a chilling

sound it was too - and they would test the Javelin's engines, which

were absolutely deafening. The Gloster Javelin was a pioneering

jet-propelled fighter aircraft that at the time was a world beater, and

it made me very proud to think that it was being built in my village. I

don't

recall ever seeing a Javelin in the skies above Brockworth, and I don't

believe they even had a runway, but then aircraft in the skies were few

and

far between in those days, and I don't really recall seeing that many

over Brockworth in my

fifteen years there. Brockworth

village grew up on the

back of the Gloucester Aircraft Company, which, although many websites

claim was situated in Hucclecote, the next village along Ermin Street

on the way to Gloucester City, was actually situated in Brockworth. The

main entrance was in Brockworth, and there were a couple of miles of

open fields and houses before you got to Hucclecote, although the

grounds of the Gloucester Aircraft Company ran along the back of these

houses and did indeed join Hucclecote to Brockworth. In 1950, the first

year I really remember anything of any significance, Gloucester

Aircraft Company was making the Gloucester Javelin, and every morning

at around ten o'clock, the air raid siren would sound - a chilling

sound it was too - and they would test the Javelin's engines, which

were absolutely deafening. The Gloster Javelin was a pioneering

jet-propelled fighter aircraft that at the time was a world beater, and

it made me very proud to think that it was being built in my village. I

don't

recall ever seeing a Javelin in the skies above Brockworth, and I don't

believe they even had a runway, but then aircraft in the skies were few

and

far between in those days, and I don't really recall seeing that many

over Brockworth in my

fifteen years there. I was more into cars, anyway, and had a little pocket notebook into which I would write the number plate details of every car I saw in the village, which wasn't very many at all. The reason for this remains unclear. A notebook with car number plates - it wasn't like stamp collecting, was it? My Uncle Ernie had a car, a Standard 8, in which he drove around the villages collecting insurance money. We didn't have a car until 1960, when Dad brought home a 1936 Morris 8 Tourer which he painstakingly stripped down and rebuilt over a couple of months. I'll tell you more about this car when we get to the Sixties... My Uncle Ed, Dad's brother, always had a car - the one I remember most vividly was his three-wheeled MG, which I hated. Cars should always have four wheels. Occasionally he would turn up on a motorbike. He was flamboyant and daredevil in a way I really admired, but he was also reckless, and thought nothing of driving around under the influence of drink, which always troubled me. But then he lived to the ripe old age of 83. He always dragged my Dad away from the house to go down the road to one of the two pubs in Ermin Street, the one at the top of the road where you went to Cheltenham, the Coach and Horses, the other actually down in Hucclecote, which was the Pine Trees; and they always came back after closing time, the worse for wear. My Mum turned a blind eye. She worshipped Dad, he could do no wrong. To the best of my knowledge he never cheated on her, although it was rumoured that that was why we suddenly left Brockworth in 1963, but neither my sister Jean nor I ever really knew the real reason. It could have been that - Dad went off to work every day to catch a works bus that took him to the Forest of Dean, where J Arthur Rank had his Xerox machine factory, and where Dad was Chief Tool Engineer.  This

was a very good job, and

although we were never what you might call rich, we never went without,

even though some things were purchased on credit, such as the radiogram

and the brand new cylinder Hoover vacuum cleaner, and my bicycle and

first guitar, of which more in another issue of Books Monthly. My Mum

was the

seventh and youngest child of Florence and Henry William Kimber. My

Gran was my only grandparent, Henry William Kimber having died in 1943,

before I was born. On my Dad's side, his Dad, Arthur Robert Norman,

joined up in 1915 and was killed at the Battle of the Somme in August

1916. His wife, Emily Kemp, died in 1929. So three of my grandparents

died before I was born. I should like to take a moment here to pause

and reflect on the importance of asking your parents and grandparents

about their family history, because when they're dead, it's obviously

too late. When Mum died in 2002, I inherited a huge box of family

photographs, some from the very early days of photography, and I don't

have a clue as to who many of them are. It was only when we started to

research our family trees that we discovered things about our families

that no one ever talked about. I always knew that Emily Kemp, my

paternal grandmother, had re-married after Granddad Arthur Robert

Norman was killed in the Great War. This

was a very good job, and

although we were never what you might call rich, we never went without,

even though some things were purchased on credit, such as the radiogram

and the brand new cylinder Hoover vacuum cleaner, and my bicycle and

first guitar, of which more in another issue of Books Monthly. My Mum

was the

seventh and youngest child of Florence and Henry William Kimber. My

Gran was my only grandparent, Henry William Kimber having died in 1943,

before I was born. On my Dad's side, his Dad, Arthur Robert Norman,

joined up in 1915 and was killed at the Battle of the Somme in August

1916. His wife, Emily Kemp, died in 1929. So three of my grandparents

died before I was born. I should like to take a moment here to pause

and reflect on the importance of asking your parents and grandparents

about their family history, because when they're dead, it's obviously

too late. When Mum died in 2002, I inherited a huge box of family

photographs, some from the very early days of photography, and I don't

have a clue as to who many of them are. It was only when we started to

research our family trees that we discovered things about our families

that no one ever talked about. I always knew that Emily Kemp, my

paternal grandmother, had re-married after Granddad Arthur Robert

Norman was killed in the Great War. She married a man called Matthews, and he was the father of Dad's brother, my Uncle Ed, the one with the three-wheeled MG. Although I didn't know why, I always knew that she had abandoned her four children by Arthur Robert Norman when she re-married - my Aunty Florrie, Aunty Ivy, Aunty Doris and my Dad were brought up by Arthur Robert Norman's brother, Leopold Septimus Norman, and his wife, Aunt Maggie. We visited them often, firstly in Hornchurch, where the rest of the Normans now resided, and later in Lyme Regis, and they occasionally came to visit us and stay with us in Brockworth. They were always very kind to me, always gave me two half-crowns, which was a huge amount of money in the 1950s, and which I put to good use by buying books to add to my growing collection. They would stay for a couple of weeks, and always had family memories to share with Dad. We never heard Dad speak about his mother, Emily Kemp; even when Uncle Leo told Dad he had been to a seance and had been in touch with his Mum, Emily Kemp, he didn't want to know. There was some bad feeling there all right. I doubt he would have told me anything about her had I asked, but at least I should have asked him about my missing grandmother. Mum and Dad married in 1939.  As I said, Mum came from a large

family, one sister and five brothers, and her eldest brother, my Uncle

Bill, was the first to discover the village of Brockworth, because the

entire family, both branches of it, were all Londoners. Dad was an

Eastender, a genuine cockney. Mum was born in Camberwell. Dad met my

Uncle John and they became best friends, and that's how he met Mum. I

know for a fact that they married in London, though I don't know which

church it was. But by the closing months of 1939, Uncle Bill was

renting a three-bedroomed villa in Court Road Brockworth, Mum and Dad

were renting rooms above Mr Ellis's general store at the western end of

Boverton Drive in Brockworth, and my Gran was renting a similar house

to Uncle Bill's in Boverton Avenue, which ran parallel to Boverton

Drive. Uncle Ernie and Uncle John lilved with Gran, both of them

confirmed bachelors. Uncle Leslie rented a house in Hucclecote, and

Mum's final brother, Albert, died at the age of two in 1916. Across the

road from Gran lived Great Uncle Ernie Kimber and his wife Grace, a

horrid woman that no one liked. She didn't like any of us, really. So,

in 1939, the entire Kimber family (and my Dad) were living in rural

Gloucestershire. My sister Jean was born in 1941 in the rooms above Mr

Ellis's store, so Mum and Dad must have moved to the three-bedroomed

villa that became our home until 1963 in Boverton Drive after that, and

I was born there in 1946,

delivered by District Nurse Doyle, who said I must be a German baby

because of my square head. The rest of the decade passed without

incident (for me) and in 1950 I started to make the memories I can now

look back on with complete fondness. Many people who write about the

1950s and 1960s come from poor families and write about deprivation and

hardships, outside toilets and sharing rooms. As I said, Mum came from a large

family, one sister and five brothers, and her eldest brother, my Uncle

Bill, was the first to discover the village of Brockworth, because the

entire family, both branches of it, were all Londoners. Dad was an

Eastender, a genuine cockney. Mum was born in Camberwell. Dad met my

Uncle John and they became best friends, and that's how he met Mum. I

know for a fact that they married in London, though I don't know which

church it was. But by the closing months of 1939, Uncle Bill was

renting a three-bedroomed villa in Court Road Brockworth, Mum and Dad

were renting rooms above Mr Ellis's general store at the western end of

Boverton Drive in Brockworth, and my Gran was renting a similar house

to Uncle Bill's in Boverton Avenue, which ran parallel to Boverton

Drive. Uncle Ernie and Uncle John lilved with Gran, both of them

confirmed bachelors. Uncle Leslie rented a house in Hucclecote, and

Mum's final brother, Albert, died at the age of two in 1916. Across the

road from Gran lived Great Uncle Ernie Kimber and his wife Grace, a

horrid woman that no one liked. She didn't like any of us, really. So,

in 1939, the entire Kimber family (and my Dad) were living in rural

Gloucestershire. My sister Jean was born in 1941 in the rooms above Mr

Ellis's store, so Mum and Dad must have moved to the three-bedroomed

villa that became our home until 1963 in Boverton Drive after that, and

I was born there in 1946,

delivered by District Nurse Doyle, who said I must be a German baby

because of my square head. The rest of the decade passed without

incident (for me) and in 1950 I started to make the memories I can now

look back on with complete fondness. Many people who write about the

1950s and 1960s come from poor families and write about deprivation and

hardships, outside toilets and sharing rooms.  I was brought up in comparative

luxury and I can only describe that bringing up as privileged. Not in

the sense that we were upper class or anything. I think Dad would have

described us as middle class, but in reality, we were proper working

class. He was a white collar worker in a junior management position. He

took the Daily Telegraph every day and he always voted conservative,

unlike the Kimber clan, who were working class through and through, who

voted Labour without fail, and who had the headquarters of the local

Labour party in their dining room every week. It was a bone of some

contention between the two families, but Dad was stubborn, and

considered himself, as I said, to be middle class. The rest of us knew

better. I hated the Daily Telegraph for a variety of reasons. Firstly,

there were no cartoons - or if there were, they were rubbish, compared

with the Daily Mirror, which had Garth, Any Capp, the Perishers, and

Jane, that scantily clad young lady whose cartoon strip I was forbidden

to read, but which Gran and Uncles John and Ernie let me read anyway.

Secondly, the sheer size of it. When I was eleven years old, I took on

a paper round, of which more later, and those Telegraphs and Times were

so bloody heavy, especially when it came to the Sunday rounds! So,

there I was, sitting on the floor in front of the radio, listening to

Listen With Mother, reading my comic, probably Jack and Jill, early in

1950, in a comfortable, modern three bedroom

house with my own bedroom and a comparatively privileged life to look

forward to. If I turned my head to the left, to the bay window, I could

see Cheeseroll Hill in the distance, a hill that was already famous all

over the country, and which would figure large in my life until we left

Brockworth forever in 1963. I was brought up in comparative

luxury and I can only describe that bringing up as privileged. Not in

the sense that we were upper class or anything. I think Dad would have

described us as middle class, but in reality, we were proper working

class. He was a white collar worker in a junior management position. He

took the Daily Telegraph every day and he always voted conservative,

unlike the Kimber clan, who were working class through and through, who

voted Labour without fail, and who had the headquarters of the local

Labour party in their dining room every week. It was a bone of some

contention between the two families, but Dad was stubborn, and

considered himself, as I said, to be middle class. The rest of us knew

better. I hated the Daily Telegraph for a variety of reasons. Firstly,

there were no cartoons - or if there were, they were rubbish, compared

with the Daily Mirror, which had Garth, Any Capp, the Perishers, and

Jane, that scantily clad young lady whose cartoon strip I was forbidden

to read, but which Gran and Uncles John and Ernie let me read anyway.

Secondly, the sheer size of it. When I was eleven years old, I took on

a paper round, of which more later, and those Telegraphs and Times were

so bloody heavy, especially when it came to the Sunday rounds! So,

there I was, sitting on the floor in front of the radio, listening to

Listen With Mother, reading my comic, probably Jack and Jill, early in

1950, in a comfortable, modern three bedroom

house with my own bedroom and a comparatively privileged life to look

forward to. If I turned my head to the left, to the bay window, I could

see Cheeseroll Hill in the distance, a hill that was already famous all

over the country, and which would figure large in my life until we left

Brockworth forever in 1963. I loved Listen With Mother. Radio was everything - it provided 99% of the music in my life until I was old enough to appreciate the 78rpm shellac discs I inherited from Great Uncle Ernie and later from Uncles John and Ernie. The radio provided singular entertainment in the form of stories, and as we didn't have a television - in fact we never had a television in Brockworth - it was a form of entertainment for the whole family for the first fifteen years of my life. Which brings me back to the start of this nostalgic journey - what was it really like to grow up in the 1950s and 1960s? The answer is, for me, idyllic. I had my radio programmes, I had my growing library of books, I had my weekly comics (of which more in the next instalment in the December issue); I had open countryside just a few minutes down the road, I had my Meccano and my Dinky, Corgi and Matchbox toys, I had toy soldiers, one of which I pretended was Tarzan of the Apes, I had my teddy bear, and I had a loving family. I enjoyed very good health except that I was prone to bouts of bronchitis, but apart from that, I was in extraordinarily rude health. And with that, I shall stop for now and carry on in the next issue of Books Monthly. December 2021:  In 1950, I left

home. I was four years old. I packed my

teddy bear, a couple of handkerchiefs, and one of my favourite Mabel

Lucie Attwell books into a small, battered old suitcase an ageing

relative had given to me as a gift, I opened the front door and walked

up the long drive to the wooden gates (shortly to be replaced by

wrought iron gates my father made himself), opened one of the gates and

stood at the threshhold of a new life. Something had upset me - My Mum

was just a couple of yards away, weeding the front garden - it was, I

recall, a beautiful summer's day, just perfect for starting a new life

away from the misery of my life in Brockworth. I intended to walk down

the road, get on the bus to the city, make my way to the railway

station and board a train for somewhere, I didn't know where, I hadn't

yet made up my mind. If you think my parents were irresponsible,

watching me open the garden gate and stand on the pavement next to the

massive telegraph pole anchored with inch-thick steel rope to the

concrete pavement, you're entirely wrong. This was 1950. No one in our

street had a car. Deliveries of everything other than the royal mail

parcels were made by horse and cart, and it certainly wasn't dustbin

day, when the men would lift our dustbins easily onto their shoulders,

then slide open the curved lids of the containers, and dump the

contents inside. The street was entirely deserted. Mum let me get a

couple of yards away from the gates, which I had carefully shut, before

gently taking my hand with a smile and leading me back inside the

garden, saying 'Let's get some of your cars and play in the earth,

shall we?' In 1950, I left

home. I was four years old. I packed my

teddy bear, a couple of handkerchiefs, and one of my favourite Mabel

Lucie Attwell books into a small, battered old suitcase an ageing

relative had given to me as a gift, I opened the front door and walked

up the long drive to the wooden gates (shortly to be replaced by

wrought iron gates my father made himself), opened one of the gates and

stood at the threshhold of a new life. Something had upset me - My Mum

was just a couple of yards away, weeding the front garden - it was, I

recall, a beautiful summer's day, just perfect for starting a new life

away from the misery of my life in Brockworth. I intended to walk down

the road, get on the bus to the city, make my way to the railway

station and board a train for somewhere, I didn't know where, I hadn't

yet made up my mind. If you think my parents were irresponsible,

watching me open the garden gate and stand on the pavement next to the

massive telegraph pole anchored with inch-thick steel rope to the

concrete pavement, you're entirely wrong. This was 1950. No one in our

street had a car. Deliveries of everything other than the royal mail

parcels were made by horse and cart, and it certainly wasn't dustbin

day, when the men would lift our dustbins easily onto their shoulders,

then slide open the curved lids of the containers, and dump the

contents inside. The street was entirely deserted. Mum let me get a

couple of yards away from the gates, which I had carefully shut, before

gently taking my hand with a smile and leading me back inside the

garden, saying 'Let's get some of your cars and play in the earth,

shall we?'I was four years old, and in all probability, I had wanted to do something that was not allowed, and, temporarily furious, I had packed Teddy and my few belongings and declared my intention of leaving home. The adventure was extremely short-lived, because I was easily persuaded to come back inside and play. Dad would have been at work, my sister Jean, four years older than me, would have been at school, and Mum was a stay at home Mum. I was always easily persuaded to play with toy cars, or to colour a picture, or to read a book, or to listen to the radio. I never left home again, much as I would have enjoyed travelling on a train. When we went on holiday, we usually caught the bus to Gloucester, then walked to the coach station and caught a Black and White coach to Victoria Station in London, and finally a second coach to Ramsgate, where we holidayed for the first fifteen years of my life, staying in a boarding house a few yards from the beach. Black and White Coaches were the most familiar to me, a welcome change from the green and cream Bristol Omnibus Company double deckers we caught into the city. The coaches were much more comfortable. We stopped at Stokenchurch in Buckinghamshire, where we had a slap-up meal including one of those little slices of yellow fruitcake with the enormous glacé cherries and the currants wrapped in sellophane, which I adored. The boarding house was run by Uncle Bert, not a real Uncle but someone my Dad knew from his childhood, and who, with his wife, occasionally visited us in Brockworth to spend a few days. We occupied one big bedroom with a double bed and two single beds, and we went out after breakfast, not returning until it was time for our evening meal.  When I was a little

older,

certainly older than four, and approaching teenage years, I was

allowe3d to leave the house and walk down to the sea front to watch the

sea coming in or going out. The long days of those two week holidays in

the summer school break were spent on the beach, where we would dig

sandcastles and romp in the sea, eat ice creams and visit the

entertainment halls where I would put pennies in slots, occasionally

winning a small prize, or play bingo, where there were more

opportunities for winning prizes; there was always plenty to do in

Ramsgate, and where we felt like a long walk, we would walk the cliffs

to the next resort, Broadstairs, which was more sedate and less

"developed" than Ramsgate. On the day we went home after our two weeks,

Dad and I would walk down for a last look at the sea before catching

the coach back to Victoria and thence back to Gloucester for the final

leg of our journey home to 72 Boverton Drive, Brockworth. The thing I

remember most about our home in Gloucester was the fact that the front

door wouldn't open. It wasn't until we were on the point of moving out

that Dad finally fixed it. I remember the interior layout, of course.

Two identical rooms, a front room and a dining room, and a small

kitchen, which contained one of those tall units with a pull-down front

and cupboards below and above. Next to that, a kitchen table on which

all of our food was prepared. On the opposite wall was the sink and

draining board, and on the back wall, a pantry, in which the fresh food

like meat and butter was stored. There was a hole in the back wall of

the pantry which was filled with some kind of mesh that allowed the

food to keep cold - no refrigerator, no washing machine. We didn't have

a refrigerator until 1963, when we moved to the three-bedroomed flat

above the shop in Stevenage - that was the same year we first got a

television. When I was a little

older,

certainly older than four, and approaching teenage years, I was

allowe3d to leave the house and walk down to the sea front to watch the

sea coming in or going out. The long days of those two week holidays in

the summer school break were spent on the beach, where we would dig

sandcastles and romp in the sea, eat ice creams and visit the

entertainment halls where I would put pennies in slots, occasionally

winning a small prize, or play bingo, where there were more

opportunities for winning prizes; there was always plenty to do in

Ramsgate, and where we felt like a long walk, we would walk the cliffs

to the next resort, Broadstairs, which was more sedate and less

"developed" than Ramsgate. On the day we went home after our two weeks,

Dad and I would walk down for a last look at the sea before catching

the coach back to Victoria and thence back to Gloucester for the final

leg of our journey home to 72 Boverton Drive, Brockworth. The thing I

remember most about our home in Gloucester was the fact that the front

door wouldn't open. It wasn't until we were on the point of moving out

that Dad finally fixed it. I remember the interior layout, of course.

Two identical rooms, a front room and a dining room, and a small

kitchen, which contained one of those tall units with a pull-down front

and cupboards below and above. Next to that, a kitchen table on which

all of our food was prepared. On the opposite wall was the sink and

draining board, and on the back wall, a pantry, in which the fresh food

like meat and butter was stored. There was a hole in the back wall of

the pantry which was filled with some kind of mesh that allowed the

food to keep cold - no refrigerator, no washing machine. We didn't have

a refrigerator until 1963, when we moved to the three-bedroomed flat

above the shop in Stevenage - that was the same year we first got a

television. There was an old gas

cooker with

an eye-level grill in the kitchen. Compared with today's fitted

kitchens and appliances, it was primitive, but we ate well, and we were

never bothered with upset stomachs because our food wasn't chilled in a

refrigerator. I don't recall the butter ever being runny or unusable.

My favourite food from a very early age was sausages, which we bought

from Mr Jacomelli the butcher in the little parade of shops at the end

of Boverton Drive. On one side of the road there was the general store

run by Mr Ellis, above whose shop Jean was born in 1941. Between then

and 1946, when I was born, the family must have moved into 72 Boverton

Drive. I was proud to know that of all the houses in the Drive, ours

and next doors - they were semi-detached three bedroomed villas, our

two gardens were far and away the biggest. Next door was a family of

six, I forget their name, but they moved out in 1948, making way for

Harold and Iris Hughes and their four children, Adrian and his sister,

and the ginger-haired twins Nigel and Norman, who were two years older

than me. They were Methodists. I don't say that detrimentally, of

course, but simply to illustrate the point that the parents seemed to

be much stricter than mine. What's more, they didn't use their front

room. What? They kept it for best. Best what? They rarely had visitors,

and when they did they were entertained in the dining room. We played

together, Nigel, Norman and I, despite our age difference. They taught

me to climb trees, taking me higher than I had ever been before, and

making sure I didn't fall. Eventually, of course, they took their 11+,

which they both failed. Harry, their father, was so incensed that they

had failed, he paid for them to attend a private school in Gloucester

near to the Cathedral; Kings' School took day students as well as

boarders, and they went there as day students until it was time to

begin their A level studies, at which point they transferred to my

school, Crypat Grammar School for Boys, where they were celebrated for

being twins, and I was the only person in the school who could tell

them apart, which earned me many bonus points, I can tell you! There was an old gas

cooker with

an eye-level grill in the kitchen. Compared with today's fitted

kitchens and appliances, it was primitive, but we ate well, and we were

never bothered with upset stomachs because our food wasn't chilled in a

refrigerator. I don't recall the butter ever being runny or unusable.

My favourite food from a very early age was sausages, which we bought

from Mr Jacomelli the butcher in the little parade of shops at the end

of Boverton Drive. On one side of the road there was the general store

run by Mr Ellis, above whose shop Jean was born in 1941. Between then

and 1946, when I was born, the family must have moved into 72 Boverton

Drive. I was proud to know that of all the houses in the Drive, ours

and next doors - they were semi-detached three bedroomed villas, our

two gardens were far and away the biggest. Next door was a family of

six, I forget their name, but they moved out in 1948, making way for

Harold and Iris Hughes and their four children, Adrian and his sister,

and the ginger-haired twins Nigel and Norman, who were two years older

than me. They were Methodists. I don't say that detrimentally, of

course, but simply to illustrate the point that the parents seemed to

be much stricter than mine. What's more, they didn't use their front

room. What? They kept it for best. Best what? They rarely had visitors,

and when they did they were entertained in the dining room. We played

together, Nigel, Norman and I, despite our age difference. They taught

me to climb trees, taking me higher than I had ever been before, and

making sure I didn't fall. Eventually, of course, they took their 11+,

which they both failed. Harry, their father, was so incensed that they

had failed, he paid for them to attend a private school in Gloucester

near to the Cathedral; Kings' School took day students as well as

boarders, and they went there as day students until it was time to

begin their A level studies, at which point they transferred to my

school, Crypat Grammar School for Boys, where they were celebrated for

being twins, and I was the only person in the school who could tell

them apart, which earned me many bonus points, I can tell you! I

was telling you about the shops

- opposite Mr Ellis's general store, where we bought our sweets, ice

creams, pop (Tizer, mainly) and toothpaste (those little round tins of

solid toothpaste that you softened with your toothbrush and cold

water), and various other items, there was the row of three shops that

ended with Jacomelli's the butcher. I believe one of the other two

shops was a ladies' hairdressers, but I can't swear to it; I have no

idea what the third shop was. We had our newspaper delivered from Mr

Lees's post office down on the main road, which was Ermin Street, and

ran from Cheltenham to Gloucester. I have no idea if this was the

original Ermin Street built by the Romans, but it was certainly a very

straight road. If you followed it the other way, as though you were

headed to Cheltenham, you came to a large roundabout, and if you went

straight on, to the East, you climbed up into the start of the

Cotswolds. Turn right and you went to Cranham Woods, and the top of

Cheeseroll Hill. Turn left and you went to Charlton Kings, the

racecourse, and finally Cheltenham. When I was four and a half years

old, I started school. I always thought that my first school, which had

one class, one classroom and about twenty pupils, was in Shurdington,

and there are plenty of references on the web about the little school

at Shurdington. But it's in the wrong direction. My most vivid memory

is of clinging to one of the poles in a double decker, hanging on for

dear life as it climbed a very steep hill after turning right and

passing Cranham Woods. Either way, I attended this one form school for

just a few months, because in the summer of 1951, Brockworth New County

Primary School was opened, Jean was in the top year, and was a prefect,

whilst I was in the bottom year. I

was telling you about the shops

- opposite Mr Ellis's general store, where we bought our sweets, ice

creams, pop (Tizer, mainly) and toothpaste (those little round tins of

solid toothpaste that you softened with your toothbrush and cold

water), and various other items, there was the row of three shops that

ended with Jacomelli's the butcher. I believe one of the other two

shops was a ladies' hairdressers, but I can't swear to it; I have no

idea what the third shop was. We had our newspaper delivered from Mr

Lees's post office down on the main road, which was Ermin Street, and

ran from Cheltenham to Gloucester. I have no idea if this was the

original Ermin Street built by the Romans, but it was certainly a very

straight road. If you followed it the other way, as though you were

headed to Cheltenham, you came to a large roundabout, and if you went

straight on, to the East, you climbed up into the start of the

Cotswolds. Turn right and you went to Cranham Woods, and the top of

Cheeseroll Hill. Turn left and you went to Charlton Kings, the

racecourse, and finally Cheltenham. When I was four and a half years

old, I started school. I always thought that my first school, which had

one class, one classroom and about twenty pupils, was in Shurdington,

and there are plenty of references on the web about the little school

at Shurdington. But it's in the wrong direction. My most vivid memory

is of clinging to one of the poles in a double decker, hanging on for

dear life as it climbed a very steep hill after turning right and

passing Cranham Woods. Either way, I attended this one form school for

just a few months, because in the summer of 1951, Brockworth New County

Primary School was opened, Jean was in the top year, and was a prefect,

whilst I was in the bottom year.I loved my time at this brand new school, and remember at least two of my favourite teachers, Miss Paige and Mr Rossiter, both of whom brought out the best in me, so much so that at age ten, I was considered good enough to sit the 11+ exam. I remember Brenda Offer, who lived in Boverton Drive, and who became my regular country dance partner. She was probably the first girl I was in love with. I remember Joan Mclaren and her older brother Gilmour McLaren. I remember Thomas Tullis, who shut my thumb in the French doors, an excruciatingly painful injury for which I still bear the scar. I remember Mr Gillow, the headmaster, who punished me for leading a revolution against the horrific lumpy custard they served us with our school dinners, and I remember his son Robert Gillow, also in my class and several months older than me, who sat the 11+ at the same time as me, and failed, much to the disgust of his father. At school break times we played games like "What's The Time Mr Wolf?", and rounders and so on - I wasn't particularly good at games, being bookish, and when we went to the playing fields for a kickabout, I invariably made an excuse to go home early so that I could sit up in bed and read my books and comics. During my time at Brockworth New County Primary School, I learnt to read and write well, and had a huge vocabulary. I read classics and adventure stories by people like Charles Dickens, Robert Louis Stevenson, R M Ballantyne, whilst at the same time discovering the joys of John Dickson Carr, John Creasey, Leslie Charteris, Dennis Wheatley, Edgar Rice Burroughs and so on. I remember our class being given a project, to write a nonfiction book about something we were passionate about.I chose Ocean-going liners and duly wrote off to companies like Cunard and P&O, asking for their brochures, which I used to write my book. I loved the idea of ocean-going liners, but never got round to sailing on one. Whilst on holiday in Ramsgate, we went, every year, on a motor boat trip out into the channel, retracing the journey undertaken by this actual boat, when the flotilla of boats and ships went to rescue the survivors of Dynkirk. The captain of the boat had actually sailed his boat to Dunkirk and had brought back twenty or so survivors before turning round and going back for more. It was something both thrilling and exhilarating to think I was following in the footsteps of my wartime heroes. Scroll down for Growing up in the 1950s/1960s Episode 2 : Episode 3 : Episode 4 : Episode 5 : Episode 6 : Episode 7 Episode 8 : In this issue, Episode 9 October 2021 - jump to the latest episode here... Episode 1 Time to start talking about music and me, I think. I was born into a musical family - that is to say, my Mum played the piano, my Dad played a variety of stringed instruments - we have a photograph of him in fancy dress as a gypsy, playing a violin, but from memory he was never that good on the violin, although he excelled on the mandolin-banjo; my sister Jean, who passed away last month, played the piano, and I played, firstly the recorder (of which more in a moment), then the violin (until the incident with the violin teacher), and finally the guitar, my basic prowess at which I managed to pass on to my two boys, who are both far superior to me; and finally, my violin playing rubbed off on daughter Samantha who went the whole hog and is a Master of Music. So, when I say that I come from a musical family, I'm not talking about more than two generations, I'm talking about my immediate family. My uncles sometimes joined in with stringed instruments such as mandolins, but more often than not they were content to sit and listen as we murdered such classics as Suppé's Poet and Peasant, and tunes from motion pictures such as The Wedding of the Painted Doll. If you were to raise the lid of the piano stool, you would find a massive pile of sheet music, all for the pianoforte. We had one in the house, and my Dad occasionally attempted to tune it, often well enough for Jean to practice her Schubert and her Chopin. There was a time when she was the most gifted musician in the house, but I like to think that when I passed grade three Violin I was starting to overtake her, and by the time I had mastered the basics of guitar playing (jazz and skiffle), she was married and living in a caravan in Charlton Kings, near Cheltenham. Of course, playing an instrument doesn't make you an expert in music. For that, you need to listen. My first instrument, the recorder, was something I was very good at, but it required me to produce a lot of spittle. So much that, my Mum and Dad, being very good with practical jokes of the variety that didn't hurt you mentally, made a cardboard box from a cereal packet (easy, really, just cut the bottom off) and tied it with string to my recorder. I was so good at the recorder (performing regularly in ensemble at my Primary School), that I was sent down the road a few doors to where Mrs Livesey lived, the piano teacher who had made such a brilliant job of teaching Jean. But, to my dismay, I was no good at piano. My left hand wanted to play the same notes, an octave lower, than my right hand, and vice versa. Later, much later, after many years of playing violin and then guitar, I taught myself to play The Old Rugged Cross on our old piano, achieving a very commendable left hand accompaniment. But my greatest love was the guitar. My earliest memories of listening to music are of Listen With Mother. This would have been from 1950 onwards, when I was walking, and looking at picture books by Mabel Lucy Attwell, and learning to read, and when my ears started to tune themselves to the rather pleasant sounds that came out of the box on the small table in the alcove in the front room next to the bay window. The time was 1:45pm, the introductory music was a few notes on the piano, and then Daphne Oxenford or Julia Lang, who both had the sweetest voices on the radio, asked "Are you sitting comfortably?..... Then I'll begin." And they would start to read to me, stories that featured characters such as Larry the Lamb and Dennis the Dachsund and their adventures in Toytown. The programme finished a quarter of an hour later, with Gabriel Fauré's Dolly Suite. The music is beautiful, the stories were especially tailored for us "baby boomers", children born after 1945 celebrations. I was a baby boomer, sister Jean was a war baby, born in 1941. I miss Jean terribly - we spoke often on the phone; she always looked after me in the early days, and we always got on famously, except for that time when I bought the Beatles' first LP, and played it over and over again downstairs on the radiogram, causing her to make her one and only ccomplaint (that I remember) to my Mum, about playing my music too loud. It was different when she wanted to play her Frank SInatra LPs, of course. But I'm getting ahead of myself. Radio was everything in the 1950s. few people had televisions, at least in our street. Our new next door neighbours, the Hughes family, comprising Ida (mother), father (forget his name), Adrian, Norman and Nigel (the ginger-haired twins) and their sister (forget her name too!), had a television, a nine inch screen which was positioned in the hall, into which we were invited to stand and watch the Coronation in 1953. I imagine they moved the TV into the hall from the lounge, which was always kept shut, except on special occasions (to which we were not privy). The parents were Methodists, very strict, and kept themselves and their home private. They kept up with the Gardners, who lived on the opposite corner, because in their opinion, we were lower in class, probably because we could not afford a television and neither could we afford a car. Both the Hughes family and the Gardner family bought brand new Ford Anglias on the same day... Norman and Nigel, who were rebellious, weren't Methodists, if anything they were unbelievers, never once went in their father's car. At least, that's how it seemed to me. Back to Radio. In those days, there was The Light Programme, The Home Programme, and The Third Programme. With the relaunch of BBC Radio in the 1960s, these became, respectively, Radio 2, Radio 4, and Radio 3. The bulk of the music was to be found on The Light Programme and the Home Programme, unless you had a love of classical music, in which case you tuned to The Third Programme. I had no knowledge or even a liking for classical music in my formative years - that came much later. As a toddler, I listened to every music programme on the radio: Workers' Playtime, Parade of the Pops, Housewives' Choice, Music While You Work, Henry Hall's Music Night, Friday Night is Music Night, Children's Favourites, Two-Way Family Favourites (which often became Three-Way and even, on occasion, Four-Way Family Favourites). Every programme on the BBC had its own theme tune, of course, and on Children's Favourites I would be regaled with all manner of musical treats, like 'Peter and the Wolf', 'The Ugly Duckling', Gilly Gilly Ossenfeffer, Katzenellen Bogen By the Sea', ''The Runaway Train', 'Teddy Bears' Picnic' 'Nellie the Elephant', 'A windmill in Old Amsterdam', 'Sparky's Magic Piano' and my of course, the Oberkirchen Children's Choir singing 'The Happy Wanderer'. As the years progressed and my musical tastes blossomed, I was exposed to simple folk tunes such as Barbara Ellen, and Bobby Shaftoe at school, and various others to which we did country dancing (one of my favourite lessons at school!). I remember one occasion when the Headmaster, a terrifying tyrant called Mr Gillow (whom I didn't like and with whose bullying son I had a run-in in about 1955) brought a gramophone into our lesson and played Smetana's The Bartered Bride Overture. I don't know why, but it made me think about listening to other music - it was exciting, electrifying, hugely enjoyable, and I knew that other music existed because, as I said earlier, we listened to every music programme going, including Mantovani, who murdered various light classical pieces. By this time, I had discovered our own wind-up gramophone, which I believe had a built-in speaker, not one of those giant horns you see in the illustrations of the period, and a stack of 78rpm shellac records of performers like Al Bowlly, Harry Roy and his Band, Jack Hylton and his Orchestra, etc., etc. There was a built-in tray holding the needles you needed to replace on a regular basis. In the next road, my Great Uncle Ernie and Aunt Grace lived. He was OK, she was horrible. But he gave me a pile of 78s to play on my newly discovered toy, for which I was very grateful, finding amongst them,, for example, a performance by Django Reinhardt and the Quintette du Hot Club de France. I was delighted to discover later that day that my Dad also had some Django 78s, and these became the flavour of the month for me, so much so that when my French teacher said we all had to give a five minute presentation (in French) to the rest of the class, I chose to speak about the amazing Django Reinhardt. He was Belgian, not French, but the language was the same, wasn't it? By this time, the world had moved on. To 45rpm single records, and 33-and-a-third rpm albums. On the way home from school in 1958, I went past Currys in the Oxbode in Gloucester. On the opposite side of the road was the massive side profile of the five-storey Bon Marché Department store. But Curry's had what I wanted - a radiogram that not only played all three speeds of record, it also had a radio built in. Our radio, the one that I used to listen to Listen With Mother on, was very old, and past its best. At least as far as I was concerned. Mum, Dad and Jean were happy with it. I was not. I was excited by the prospect of being able to put on an album and not have to get up to change the record, but to sit and listen for anything up to a half hour. In those days I could nag for England, and I nagged and nagged and nagged until Mum caved in and went to Currys and signed a hire purchase agreement for the radiogram. Once it was installed, I had other things on which to spend my pocket money and the money from my paper round besides books and comics. And music was starting to become much more important to teenagers like me. Up till now, we had to get our popular music fixes from Radio Luxembourg on frequency 208. I remember the first LP record I bought - it was a truncated performance of Beethoven's 5th Symphony on the Embassy Record Label, which was exclusive to Woolworths. I'd been with my Dad to a working men's club, which was a smoke-filled room in the middle of Gloucester, where a couple of hundred men stood and listened to a gramophone record recital of the symphony. It blew my mind! And once we had the radiograme, I simply had to have it. Years later I started to buy Classics for Pleasure LPs and discovered that the Embassy 10-inch record missed all of the repeats, and was actually very poor value for money. But at least my record collection was up and running. Some record purchases were hit and miss in those days. Everyone in the family loved traditional jazz, and in the very late 1950s, we heard a performance of Blaze Away, a John Philip Sousa march, by a new band called "Mr Acker Bilk and his Paramount Jazz Band". There was, in those days, I think, a radio programme devoted to jazz. I was duly sent out on Saturday morning to hunt down a copy. In Gloucester, there was Hickey's Music Shop, of which more later, and the Bon Marché department store. Hickeys didn't have the record, and neither did Bon Marché. What the latter did have was a performance of "Whistling Rufus" by Chris Barber's Jazz Band, and with the money Mum, Dad and Jean had given me to buy Blaze Away, I bought Whistling Rufus. There was much disappointment. But in the end I was forgiven, because my Melody Maker newspaper revealed that Blaze Away was on an album and had not been released as a single. By this time, I was hooked on Acker Bilk, and it coincided with "trad jazz" becoming the hottest thing in British music making. Dozens of new bands surged onto the market, with Dick Charlesworth's City Gents, Terry Lightfoot's Band, The Dutch Swing College Band, Chris Barber's Jazz Band, Kenny Ball's Jazz Men, and Mr Acker Bilk and his Paramount Jazz Band, to name just a few. I don't know if it was the name of the band, or the amazingly different and beautiful clarinet of Acker's that hooked me, but for me his was absolutely the best trad jazz band ever, and I set out to follow him and to collect his records. It was about 1961, when Acker changed record labels from the Pye Blue Jazz label to EMI, and at that point, he appointed publicist Peter Leslie, a literary genius, to handle his promotion and to write his record sleeve notes. There is nothing quite like an Accker Bilk sleeve note, which I am in the process of preserving on a special page in Books Monthly. The trad jazz phenomenon was comparatively short-lived, although Acker did shoot to international fame and acclaim with the gorgeous and very memorable Stranger on the Shore, which ensured he was never forgotten, and must have provided him with adequate funds to keep him in comparative luxury until he passed away in 2014. What followed trad jazz in Britain was quite extraordinary, and changed music forever... The thrill of finding out about new albums (and even the occasional single record or EP) by Mr Acker Bilk and His Paramount Jazz Band came about by me buying, every week, the Melody Maker and the New Musical Express. As I recall, there were sections on traditional jazz - and modern jazz, which I abhorred, always have, and always will - in both papers, which regularly listed the top bands, as voted for by the readers, and even twenty or so years after Django Reinhardt and the Quintette disbanded, they still figured in the top tens, because people with longer memories still voted for them. In 1958 or so, Ken Colyer's Jazz Men were still dominating the traditional jazz scene; Acker Bilk had played with them for a few months in the early 1950s before forming his own ensemble, and in their early days, they specialised in "jazzed-up" versions of Sousa marches, such as Blaze Away, Under the Double Eagle, etc., etc., which were released as 78rpm shellac records on the blue Pye Jazz label. Then in 1960, Bilk employed Peter Leslie, an up and coming pulp fiction writer, to be in charge of his publicity. He changed labels, to EMI; Leslie had the idea of dressing the band members in fancy waistcoats and bowler hats, about which I have written extensively on the Acker Bilk Sleeve Notes Page of this magazine, and which has been updated this month with a further selection of Acker's album notes written by Peter Leslie. That same year Acker's single SUMMER SET reached number five in the UK charts, and the floodgates of traditional jazz in Britain were opened. The Wikipedia page says that bands such as Acker Bilk's, Kenny Ball's and Chris Barber's tried to revive traditional jazz in Britain. I know enough about traditional jazz to know that this wasn't a revival - traditional jazz had always been popular with purists, but there was only one Golden Age of traditional jazz in Britain, and that was in the early 1960s. Those bands weren't "reviving" anything, they were playing the music that they had always loved, emulating their 1920s heroes (Jelly Roll Morton, King Oliver, Louis Armstrong's Hot Five etc.), and the British public liked what they heard and trad jazz became the dominant music genre for at least a couple of years, fading away in 1962 as the Beatles wrought the biggest revolution in popular music not just in Britain but all over the world. The 1920s in Britain had seen the boom in "swing" orchestras, like Harry Roy, Jack Hylton etc., and this genre also boomed in Britain in the early 1960s with The Temperance Seven. But the dominant two bands were Acker Bilk's and Kenny Ball's, who had a string of top 40 hits. For me, there was only ever Acker Bilk - or Mr Acker Bilk, as Peter Leslile defined him - and his Paramount Jazz Band. They were far and away the very finest musicians on the trad jazz circuit, and if you listen to Jelly Roll Morton's classic single "Doctor Jazz" and compare it with Acker's "Stomp Off, Let's Go", you can hear what Acker was trying to achieve, and how brilliantly he succeeded. There is footage on YouTube of Acker and his band playing "In a Persian Market Place", a light classical "bonbon" by Ketelbey, arranged by Acker, showcasing the brilliance of the Paramount Jazz Band in all its glory. I urge you to watch it, it is terrific, and shows an ensemble at the top of its game. The other reason for my choosing Acker above all others in the trad jazz field is the plethora of literature produced by Peter Leslie's BILK MARKETING BOARD, which was the name of the publicity machine that ensured that Acker dominated the trad jazz phenomenon that swept Britain from 1960-1962. When Acker wrote a tune which he called "Jenny" after his daughter, (subsequently renamed Stranger on the Shore to accompany a hugely successful children's TV serial) I was delighted, because it meant that my hero (who hailed from the West Country, just as I did) would still be dominating the charts even though music was changing in Britain. The announcement of the album, with Acker backed by the Leon Young String Chorale, was made in the NME and Melody Maker, with the caveat that it would be issued in the United States about five months before it would be released in Britain. I was by that time a subscriber to a record company - like the Companion Book Club, which sent you a monthly selection which you could keep or return - and they also announced the US release of the Stranger On the Shore Album. I ordered it through them, which meant that I had the precious LP in my hands five months before it was released over here; and I treasured it just like all of the other Acker Bilk albums. The sleeve notes were again written by the marketing and literary genius, Peter Leslie, and you'll find this on the Acker Bilk page in Books Monthly, too. Trad Jazz, and particularly Acker Bilk's renderings of it, have remained favourites of mine right up to the present day. Most of those brilliant Acker Bilk albums have been released as CDs, but the CD producers have not recognised how important the sleeve notes were and are, which is why I have taken it upon myself to reproduce them in Books Monthly. It is literature, after all. The late 1950s and early 1960s are imprinted on my memory as my Golden Age of music - or discoveries, of passions, of formative years. In 1958 my dear Gran died. I only ever had one grandparent, the other three all died before I was born. She was precious to me - I have only the fondest memories of her. In 1958 I was eleven years old (when she died - I reached twelve later in the year). Mum and Dad decided I might be too young to attend her funeral, and so I was packed off to spend the day with sister Jean in her place of work in Cheltenham, in a Grace Bros., style store called Wolfe and Hollander, where she worked as a secretary. I was given a ten shilling note (a fortune in those days) and told to go and spend it, to buy something I really wanted, so that the day would be remembered as a good one, and not as a dark one, the day they buried Gran. I went first into a branch of W H Smith and bought THE ADVENTURES OF SHERLOCK HOLMES, and then into a record shop, where I bought THE BALLAD OF TOM DOOLEY by the KINGSTON TRIO. I was heavily into my music by then, books and music were my principal hobbies. When the weather was too bad for outdoor play, like football, I was happy to sit in the front room playing my records and reading my books.  Like my three children

after me, I

always maintained that I could do my homework with my music playing in

the background. It worked for me, and it worked for them! At school,

the arguments raged about who was best - Elvis Presley or Cliff

Richard. One of my rivals for being best at Spanish, a boy we called

"Pedro" Smith (Smith was his real name, Pedro was his nickname, first

name was really Peter), insisted on championing Elvis, but for the

purposes of just being different, I championed Cliff Richard - even

though he didn't interest me at all. If anything, he was a bit wet for

me, but I was happy to debate the various records of the two men who

dominated pop music in 1958 and on into the beginning of the 1960s. In

1962, recovering from my abuse at the hands of the peripatetic violin

teacher, with whom I reached and passed Grade 3, I was looking for a

musical challenge, for the violin had lost its appeal. I found an old

guitar in a cupboard upstairs at home, and tuned it so that it played a

chord. I spent hours teaching myself to play, sitting in front of the

big mirror in Mum and Dad's room, and then realised that I should

really be tuning it properly. This I did, and set about teaching myself

all over again, sometimes with the aid of the Bert Weedon book,